Before we get to the Pairumani farm, I should mention a little about dairy and Cochabamba. Cochabamba is known as the breadbasket of Bolivia, and it has been since the time of the Inca and likely even before. Cochabamba is one of Bolivia's valley regions, with a climate that reminded me of Southern California in many ways except for one: Cochabamba gets enough rain.

Dairy is not at all native to Bolivia, and non-European peoples are often lactose intolerant as adults. (In fact, lactose intolerance is the norm, and those of us who tolerate milk beyond childhood are the exception.) Additionally, dairy production in the tropics is difficult. I've heard many times that the most productive dairy breeds do not tolerate the heat very well, and the breeds that are well adapted to the tropics do not produce very much milk. But Cochabamba's pleasant climate is just fine for the highest producing dairy breeds, and we saw Holstein cows almost everywhere we went around the area when we were outside of the city center.

The Pairumani farm has about 500 hectares and belongs to the Simon I. Patiño Foundation. It has a pediatric medicine center, a research center that works on non-GMO legumes and cereals, a seed center, and the model farm, which we visited.

Simon I. Patiño, whose land this is, was one of the ten richest men in the world in the 20s and 30s. I believe he discovered the tin that started the tin boom in Bolivia. He was poor prior to that, and was not part of the Bolivian elite. Once he made his money, he left for Europe. He bought this land in 1920. Patiño died in 1947.

Patiño owned about 5000 hectares in the Cochabamba area. He wanted to make this a recognized agricultural area. He introduced new varieties of plants and paid for students to study agronomy abroad in order to develop Bolivia's human resources in agriculture. In the 1952, the 5000 hectares were redistributed. But 500 hectares remained as property of the foundation.

The Seed Center

Before the presentation, I poked around a bit:

A bull - this guy was all alone and bellowing non-stop. It sounded like he was screaming.

Close-up. Here, they don't remove the cows' horns.

Sheep. I asked what they were for and I was told they were here to have blood taken from them for use in one of the labs.

Horses.

Pigs were here. I asked where the pigs are now and they told me they ate them.

This was one of the first dairy production projects in Bolivia. In 1935, 400 head of Holstein cattle were brought from the best dairy farms in the U.S. and Canada. Until the mid to late 1980s, they were intensively producing dairy. In 1999, they began converting to a "agrobiological" model thanks to an agricultural study that was done, realizing that the soils were being degraded, and a lot of the cattle were sick too.

I was feeling very critical of the fact that the cows are not on pasture (which would not be possible based on the number of cows they have compared to the amount of pasture they have). But when we asked questions, we found that this dairy was already "radical" in Bolivia. The conversion they did from the former, industrial model to this model brought them a lot of criticism and ridicule from the agricultural establishment.

They grow 230 hectares of forage, cereals, and vegetables, using composting and crop rotation. For the animals, they use no hormones and they use homeopathic medicine on the 240 cows they have today. In 2009, they established a department of "research and distribution" in which they bring in students to do their dissertations by studying the farm. They also train their staff in their techniques and do education to the public. (When we asked about their land, they said they also have 130 hectares forested, mostly in Eucalyptus.)

Here, they use no GMOs, but they don't take a political position for or against GMOs. They think that more research is needed before making that call. They are part of a movement of organic products (Association of Organizations of Ecological Producers of Bolivia, AOPEB) and AOPEB has been vocal against GMOs.

They told us they are involved with the Asociacion de Criadores de Ganado Holstein Bolivia ACRHOBOL, which is a Bolivian conventional dairy organization (Association of Holstein Breeders of Bolivia). This gives the farm credibility among the wider agricultural community. They told us that their farm is seen as a somewhat antagonistic force, and at first when they converted, they were told that this model was bringing Bolivia back fifty years.

But now they've been able to earn the community's respect, and other producers are interested in their production methods. They are in fourth place for dairy production in Bolivia according to their statistics. (The others ahead of them are conventional producers.)

They told us that they had always had Holsteins, and it was really difficult in the first place to change their model so radically, and changing the breed of cows would have been even more complex. Holsteins are almost always the industrial cow breed of choice, although you do see them frequently enough on sustainable farms.

They no longer remove the cows' horns, and when they made that change, it caused a bit of a scandal at the local level. They said the first three years of their change were full of lots of debates and discussions at the local level. Within ACRHOBOL, they had debates over whether the Holstein is a living being with animal instincts, or just a milk producing machine. When they made the change, they began talking about the animals as living beings, and not just genetic material. (They mentioned that there was a study recently that showed there were more allergens present in milk from cows who had their horns removed than cows who retained their horns.)

When they made the change, they began focusing on the quality of the milk. Since then, the big dairy company in Bolivia, Pil, has implemented quality standards, and they have rejected many producers' milk. (Pil has a monopoly and monopsony of milk in Bolivia. They buy 150,000 liters (39,625.8 gallons) of milk from 4000 producers per day in Cochabamba.) This farm produces 2,000 liters (528.3 gallons) of milk per day.

One of the health indicators they use here is the level of mastitis. Some intensive systems have up to 25% mastitis, and here they have less than 2%. In ACRHOBOL, some farms have up to 14% miscarriages. In 1998, before the conversion to this model, they had up to 20% miscarriages. They now have 2% miscarriages.

One of the buildings that houses the cows. They told us they are historic buildings that they have restored.

They noted that the ideal would be allowing all of the cows out to pasture, but they do not have the pasture needed to do that. Some of the young animals are allowed out to pasture, but mostly the animals are confined. They only have 30 hectares of pasture.

When they talk about producing a high quality product, they mean three things: healthy soils, healthy plants and forage with no chemicals, and healthy animals. Without very much marketing, their milk is in the highest demand. It's used locally by hospitals and many pediatricians in the area recommend their milk specifically. They are also involved in the maternal subsidies, a program similar to WIC in the U.S.

They noted the irony, that when they started, people thought there was no way they could succeed, but now they cannot produce enough to meet demand. The milk is only available within Cochabamba department, and it can be purchased through the maternal subsidy program or at supermarkets. It's sold as "Pairumani Agrobiological Milk." They told us they are considering helping other producers convert to their model and then purchasing that milk to sell under their brand, but they are proceeding with caution.

There are 58 workers here and many live here on the farm. The farm pays for all of the healthcare of the workers. We passed some of the worker housing on our tour. While we didn't see the indoors, the outside looked very nice.

The heifers - from 6 to 24 months of age - are kept in one area. Then they have a maternal area somewhere else. The cows in production are kept in groups of low, middle, and high production. In the middle, they keep the baby calves, from zero to four months.

Baby calf.

The area the houses the calves.

The milking parlor.

They go to a waiting area before they are milked so they can relax. This is to allow a natural hormone - oxytocin - to be released so the cow can produce milk. Also, adrenaline prevents the milk from descending. They don't allow any yelling or hitting the cows by the workers. In the past, the workers sometimes mistreated the animals. But with the change in management, they told the workers that the animals have feelings, that they suffer and get sick, and must be treated well.

They said that here, the infrastructure is adapted to the animal and not the other way around. They said for feeding, they try to reproduce how animals eat out in the pasture. They are careful to protect the animals from hitting their horns when they are trying to eat. They are raising bulls because they are important to the system. They transmit pheromones, and they are used in reproduction.

This farm milks the cows twice a day using machines. (Industrial farms in the U.S. milk their cows three times a day, which allows them to get more milk from the cows.) In the old industrial system, the cows were only kept for three lactations, but they keep the cows for six or seven lactations. (In the U.S, a cow might be kept just for one or two lactations on an industrial farm, but I've been to small, organic farms that keep cows for 10-11 lactations or more.)

The back end of the cows

The front end of the cows

I took photos of what the cows were being fed:

Wheat

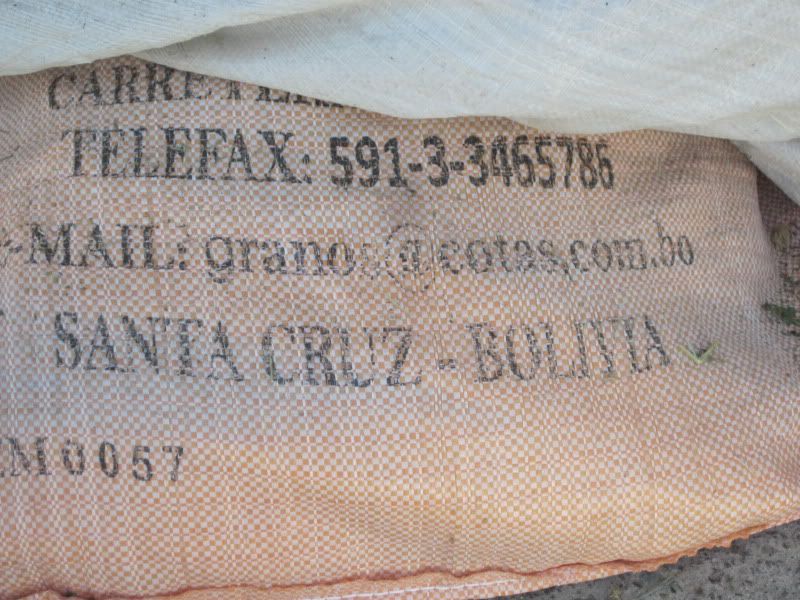

Something from Santa Cruz, probably soy.

Definitely soy. From HiPro Feeds?

Yum - that looks like good cow food.

The cows think so too.

As an intensive system, they produced 450,000 liters of milk per year here. Now, they produce 750,000 liters per year. And that increase happened with the change in systems and without an increase in the size of the farm. They went from 1,500 tons of alfalfa with chemicals to 3000 tons without chemicals. In the old system, 60 cows in production produced 21-22 liters per day. Now they have 100 cows in production.

They also showed us their homeopathic and herbal medicine lab. They said that the proper management of the farm should solve 95% of the cows' problems - but the medicine is here for the other 5%. The herbal medicines include juices, infusions, vapors, and tinctures. For example, they use a tincture of garlic and onion inside the udder for mastitis. They use calendula oil for inflammation. They also put flower buds from ceibo in the animals' food to promote fertility. They said any kind of flower would work for this.

More than 46% of their milk is sold as yogurt, which has a high added value compared to fluid milk. With yogurt, they double or triple the economic value of the milk. Consumers prefer yogurt here in Bolivia, often because they do not have refrigerators and they can keep yogurt at room temperature.

Yogurt.