The day before, Francis and I rode motorbikes to get to the health clinic and on the way home, I noticed tons of school kids staring at me. Kenya used to be a British colony so I hadn't suspected that there would be people around - many people for that matter - who had never seen a white person. Or to use their word for it, a mzungu. But from the stares I was getting from the kids, I was obviously something pretty interesting and probably funny looking as well. I just waved at them in a friendly way as if I didn't know there was anything strange about me.

So on Day 6 when Francis took me back in the same direction on motorbikes again and we visited a school - probably the very same school all the staring kids from the day before attend - I was a little more prepared for the reaction I got. But not entirely.

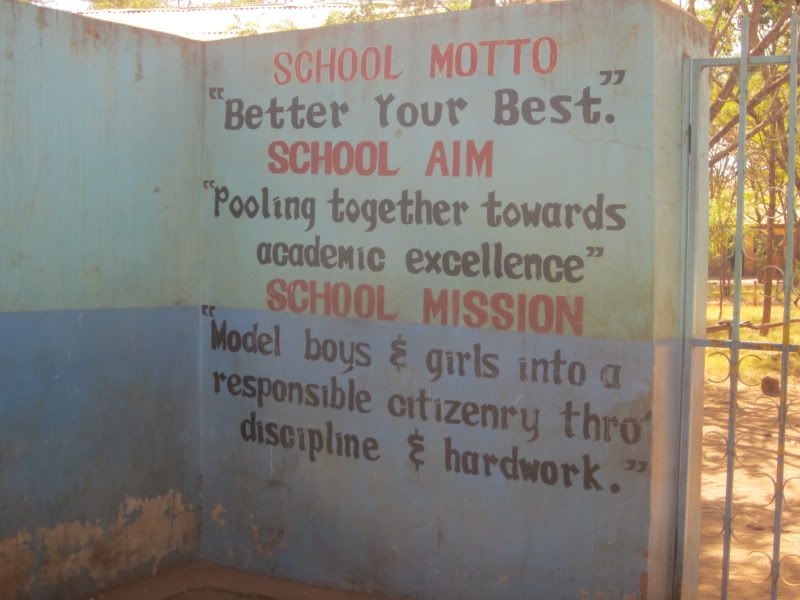

We entered the school grounds at Peter Kariuki Primary School and I swear to god, every single kid in the school crowded around me. Adults in the countryside were more reserved about seeing a funny looking mzungu, but the kids did not hide their curiosity.

Some of the kids were lacking shoes, and many of them were dirty and wearing worn out uniforms. This is not the norm for Kenya. More than the people of any other country I've visited, Kenyans are CLEAN and WELL-DRESSED. Even in the Kibera slum, the people look nice. In Kibera and everywhere else, they looked even nicer than I did. I mean, I shower regularly and sometimes even comb my hair and I don't intentionally wear clothing that is dirty or has holes, but Kenyans have their hair done nicely and the men wear suits and the women wear skirts. So to find a group of kids that were not clean and well dressed, well, to me that sent a strong, clear message. These kids had no other options. If they had the ability to dress well and clean up, they would have.

I asked if the kids wanted me to take their picture, and they elbowed each other and shoved their way in front of one another until I took it. Then the garden teacher came out to greet me and told the kids that only a certain group should follow us and the rest should go back to class or wherever they were supposed to be.

The kids, each more eager than the next to be in the photo.

We walked back to the small garden and I had a hard time getting any photos because the kids surrounded me entirely. The garden teacher explained that they have just started this demonstration biointensive garden to teach the kids - and, through them, their parents - how to grow more food in a small space. But they lack water and since it's now the end of the dry season, there wasn't much going on in the garden at all.

The garden

As a Southern California, I found that understandable. It's dry here for much of the year too and even though I have a garden hose with all the water I could ask for, there's just nothing like the rain. Rain is magic if you grow food. The plants germinate better, grow better, everything is better. I always prefer to wait for the rain to start my plants instead of watering them if I have the choice. The difference between me and the school of course is that a) if my plants don't grow, I can buy food at the store and b) if it really isn't going to rain and I really want to get my plants started, I do have water to irrigate with.

The kids and their garden

They asked me to say a few words to the kids, so I did. I told them that I love to grow the same vegetables that are popular in Kenya, and I asked if they liked pumpkin, beans, spinach, cabbage, maize, and sukumawiki (kale). I told them we love to eat those foods in America too. I asked if they would teach their parents how to grow food the way they learned at school, and the kids said yes. I realized later how naive I was to say such a thing, since many of the kids do not have parents, thanks to AIDS.

Then the teacher asked me if I had heard of the Scout movement, and I said no. Was it the same as Girl Scouts and Boy Scouts in the U.S.? The teacher began by saying that it was founded by Lord Baden-Powell. Oh my god! That IS the same scouts as we have in the U.S.!!! And then an idea started forming in my mind.

The kids have to get water from 5 km (3 mi) away because the school doesn't have very much. They have a few water tanks for the students with disabilities and for emergencies, and they have a well that doesn't work. The person who made it did a shoddy job on it and didn't drill deep enough or something, so that water doesn't come out. But they have it partially dug and there is a pump. What if our Scout troop could raise the money so they'd have a well? Or at least an extra water tank or two??? And then our Scouts could learn about the lives of Scouts in other countries, children just like them who lead much more difficult lives.

While I was cooking up this idea, the Scouts did a demonstration for me, singing a song, marching, and saying the Scout pledge in unison.

Scouts

Scouts

Students

School grounds

Then we left the kids and went to meet with Francis, the Deputy Head Teacher. As we walked, several of the kids tried to touch my skin and even pull my hair.

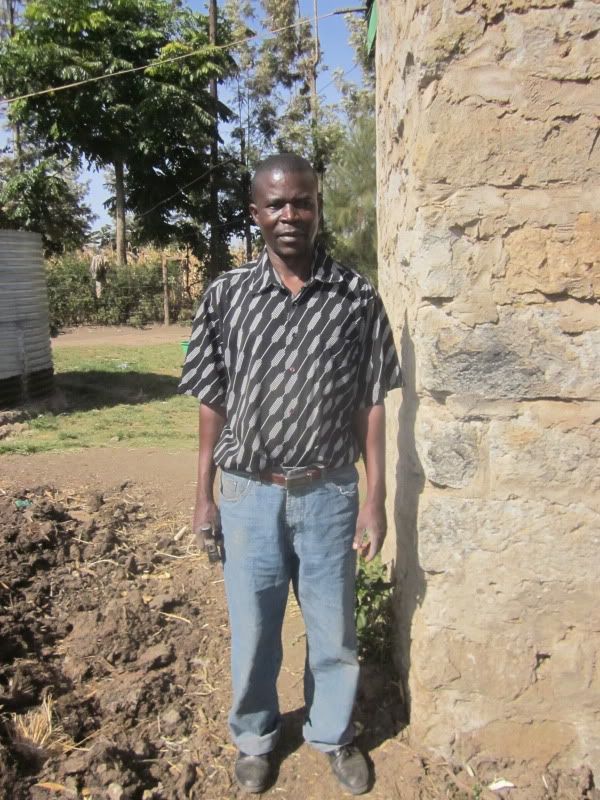

Francis, the Deputy Headteacher

Francis told me the conditions the kids faced in their homes. Several were orphans (often due to AIDS), and in some cases, the parents were alive but had just abandoned the children. Many orphans were cared for by elderly, feeble grandparents, but some were in child-headed households. Many kids, even those with parents, came from families that were too poor to feed the children breakfast. The school had a bit of maize to provide a few of the most vulnerable children with some ugali (porridge) for lunch, but most of the children ate nothing for lunch at all. Some ate only dinner each day, if that.

The kids walked to school from as far as 6-7 km away, some doing so without shoes. Particularly those in child-headed households but perhaps others had to work after school just to get enough money to eat a little bit. Some carried water for money, others worked in a nearby quarry. "Isn't that dangerous?" I asked. The response I got was basically a (much) more polite version of "Duh." Yes, it's dangerous. It's not work a child should be doing. And some kids just try to steal a pineapple and sell it to get a little bit of money, probably from Del Monte's huge plantation.

Later in my trip, someone told me that Del Monte had security dogs that attacked and sometimes killed people who tried to steal pineapples. A look at Kenya's National Assembly's record from 2000 confirms this (and again here). There's more from 2009 here and here but it's not available unless you subscribe. It seems that the problems occurred in 2000, and hopefully Del Monte decided that the dogs were bad for its image and that it was more profitable to lose a pineapple or two than to have guard dogs that murder would-be thieves.

The school does what it can for the kids, but they don't have the resources to give the kids the food and water they need. Water is the key, because with water, the school might be able to grow some food in the garden. With water on site, perhaps some of the kids won't have to walk 5 km to fetch water and they can spend that time learning instead. However, water's a small start, truly. The kids need food and beyond that, they need healthy, loving parents and they need to be able to be children without having to work in a quarry or stealing pineapple just to eat.

Since I visited the school, I asked what it would cost for them to finish drilling the well. They provided me with an estimate of $20,000, which I suspect is an overly large estimate. Kenyans like to go big at first and then expect they will have to negotiate and compromise in the middle. And they tend to think that anyone with white skin is loaded with cash.

Francis of SARDI then talked to the school and they sent me a revised estimate of $3,300 to buy two very large water tanks and set up water harvesting, a more sustainable approach and also a much easier amount of money to raise. Now that I'm back in the U.S. I am talking to our local scout leader, who is very enthusiastic about the project.