The War on Drugs met me in Bolivia and followed me home. Day 12 was my last day in Bolivia. Most of our group - everyone except for our guide, Tanya - left on an early morning flight to Miami. There are two ways to get to Bolivia (through Miami or through Peru) and I had a 5pm flight to Lima. With half a day to spend enjoying La Paz, Tanya suggested we start by visiting

El Museo Nacional de Etnografía y Folklore and then head over to the Coca Museum. So we did.

Growing Coca

At the coca museum, we saw pictures of coca production, and Tanya (my friend who was with me, who has lived in the region where coca is grown for traditional uses, i.e. chewing and tea) told me about them as we looked. She told me that coca is grown in terraces called huachus, and small coca plants are referred to as "wawa coca" - literally baby coca, using the Aymara word for baby.

An article called "The Coca Field as a Total Social Fact," Alison Spedding argues that, "The integration of coca with the local ecology and social structure of the peasant family and community is such that it is virtually impossible for it to be replaced by any other crop." She writes about coca production in Yungas, which was done by indigenous people even after the Spanish came. The Spanish coca haciendas were mostly near Cuzco (in Peru), and those haciendas supplied the mines with coca. According to Spedding, there were some haciendas near Chulumani (in Yungas) before the 1700s, but mostly the haciendas came to Yungas in the 1700s.

Spedding describes how coca integrates into peasant life as follows:

From the preparation of the original nursery, it takes two to three years for a coca field to start producing; its maximum productivity comes in the first ten years of life, but if it is well cared for it can go on producing for thirty or forty years. A peasant couple begins to plant coca in the first years of their marriage. By the time the fields come into full production, their children (who start to help with the harvest from the age of six or eight years old and harvest almost as well as adults), can help them, and the fields go on producing until the children are grown and have coca fields of their own. Coca is thus integrated into the life cycle of the peasant household. In the semitropical zone, it gives three harvests a year, does not need irrigation, grows on very poor leached soils that are not fit for other crops, is unaffected by drought and very little subject to disease or pests. It thus provides an all-year-round income and full employment for all the family - the men plant the fields and weed them, the women and children harvest them.

Spedding adds that the peasants here also produce plantains, cassava, bananas, and walusa (a kind of taro) to eat and coffee and citrus to sell in addition to coca.

In another excerpt, she describes coca cultivation:

From August or September people begin to clear land and then dig it over for the next year's fields. In November and December they go to pick seeds. January to March is the planting season, and from June to August aged fields are pruned (pillu) to allow them to regenerate, while the coca harvest goes on all year round and, above all for women, is the dominant activity in their lives.

Because of the strong link of coca production and family life, Spedding says "Abandoning coca thus implies a rejection of forms of family life which establish the basis of daily existence and collaboration in the most intimate personal relationships."

Perhaps what is most interesting is the terminology of coca, which compares it to family roles. Spedding says:

After four or five years of repeated harvests, however, the bushes get leggy, the branches weak, and the leaves become very small; they are described as qaqa, 'stammering.' At this point they are pruned down to a stump a couple of inches high, which is filed down to a point and cleaned of all the lichen that accumulates on all woody plants in Yungas. This operation is called pillu. Six months to a year later new branches have sprouted a point where they can once again be harvested.

A plant is wawa coca until its first pillu, after which it is called mit'ani, which means "owns a harvest." However, it's also the title of the woman in an hacienda tenant couple from the pre-1953 land reform era. The coca plant is thus being compared to a woman who "serves the owner of the land she occupies." Spedding goes on to mention a taboo in which menstruating women may not enter the room where coca seed is stored. While the seed is stored, it becomes covered in mold. The stored seed represents a germination (almost like a fetus growing in a womb) and symbolically, they do not want this to come into contact with menstruation, "the physiological converse of pregnancy."

When most of the coca plants have died, the field may be dug up and replanted, but the surviving old plants are left to remain and they are referred to as

awicha or grandmother. Spedding says: "Later, the children one by one marry and leave home, and eventually the aged parents are left with the remnants of their coca fields which are now awicha, grandmothers, like themselves, but still adequate to cover their much reduced requirements."

There is one last set of analogies here. Fresh coca is compared to a corpse that is hot and stinking (

junt'u and

thuksa). The fresh coca has "a penetrating, bitter, and almost nauseating odor." These leaves are stored in the same part of the house where corpses lie in wake. Once it has dried, it is thought of as a "beneficial ancestor," similar to dried corpses of ancestors that were part of Andean culture before the Spanish showed up and put a stop to that.

Nutrition of Coca

What I haven't mentioned yet is the important

nutrition role coca plays for people of Bolivia. 100 grams of coca has 305 calories, 18.9g protein, 14.4g fiber, 1540mg Calcium, 911mg Phosphorus, and 45.8mg Iron. The numbers I quoted here are those I wrote down at the Coca Museum, which differs from the numbers on their website. But the point remains that coca is a good source of calcium, phosphorus, and iron, as well as several vitamins. And often it's the only food that fills these nutritional needs for Bolivians.

Cocaine, Again

Despite the importance of coca in Andean culture, the government has a history of attempting to crack down on coca production, or at least work with the U.S. (who tries to do so). The U.S. often promotes alternative crops for coca farmers to grow. There has also been out and out coca eradication, where poor peasants have their fields wiped out. What I heard a lot about was more or less a fancy form of bribery. The U.S. tries to get the people to commit to leaving areas coca-free and in return they do things like build roads. While the DEA has been booted from Bolivia, USAID remains there and does play a role in the War on Drugs.

Here is one story about U.S. funded coca eradication efforts:

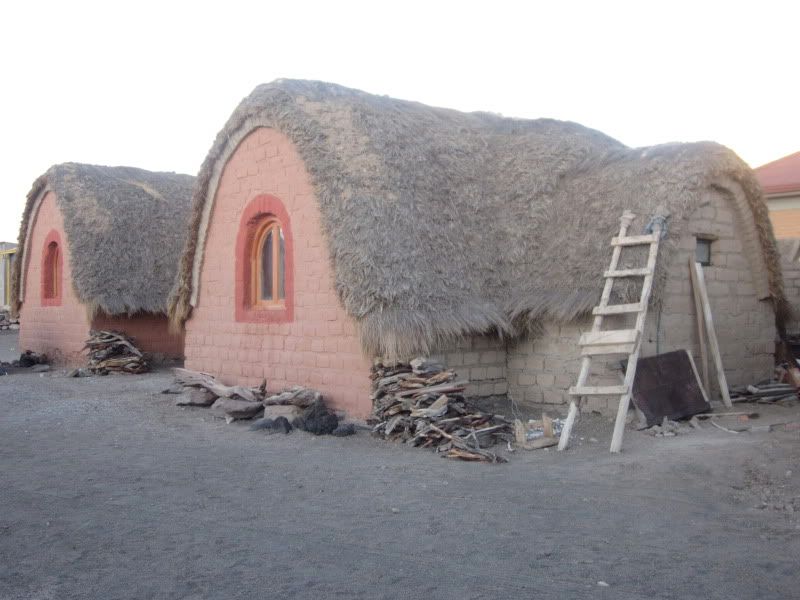

As we thread our way into the center of La Paz, Salvador tells us Frutoso's story. U.S.-funded and - trained Bolivian soldiers eradicated the man's coca-leaf crop as part of the War on Drugs, driving him from poverty to the brink of starvation. Like tens of thousands of other Quechuas in the tropical Chapare region, he lives in a mud hut full of children, surviving off his few acres of coca leaves, the only crop with a strong enough external market to maintain his family.

The United States and Europe offer Frutoso and other Bolivian coca farmers "alternative development" to help them switch to crops like papaya or heart of palm. But such trades are often disingenuous. There is often no market for these crops; this was the case for Frutoso. He planted "alternative development" bananas, tended and harvested them - but there was no one to buy them. He and other frustrated Indian peasants blocked a highway with rotting fruit. U.S.-paid Bolivian soldiers gave the Quechuas two minutes to clear the road before spraying the group with bullets. The protest leader was killed, and Frutoso's leg was filled with shrapnel and had to be amputated.

- Whispering in the Giant's Ear by William Powers, p. 206.

Frutoso now farms with one leg. Another source, the anthropology book I quoted from in the previous post, notes that as eradication efforts heat up, coca farmers penetrate deeper into uncultivated parts of Bolivia, which results in deforestation as well as the endangerment of indigenous peoples living there. (While the Quechua and Aymara are the largest indigenous groups in Bolivia, there are MANY of small ones.)

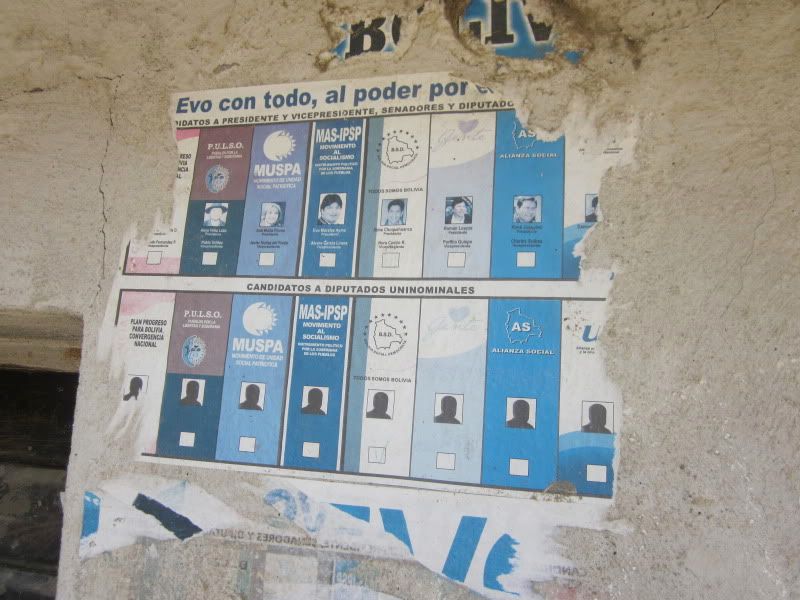

In 1985, there were 28,000 miners laid off after a "structural adjustment" (thank you World Bank!) and most went to Chapare to grow coca. These miners were already a radical bunch; they led the Revolution in 1952. I believe the family of Evo Morales was among this group. I know he was originally from Potosi but then went to Cochabamba at some point early on, and before his success in politics he was a cocalero.

In 1988, Bolivia passed Law 1008 ("ley mil ocho") which designated an area in Yungas as the traditional growing zone, and allowed for 12,000 hectares of legal coca growing to meet traditional needs. Outside of that zone, coca was set for eradication by manual or mechanical means (no herbicides) with no compensation to the growers. You can imagine that this went over well with the cocaleros. Not. Although there are nuances to this, as there seems to be somewhat of a rivalry between Yungas and Chapare, and the coca growers in the Yungas were basically given a government sanctioned monopoly on coca growing based on this law, if it were fully and effectively carried out. More recently, Evo Morales has declared that no matter what, everyone has a right to grow a small amount of coca. While I was in Bolivia, he acknowledged publicly - in Chapare - that

some coca actually does go into narcotrafficking.

I'm not sure how much coca is grown in Bolivia, but it's far more than the estimated 12,000 hectares that would meet traditional needs. The stories I heard about towns that were known for cocaine production is that the locals generally don't like to talk about it, as if it's the dirty family secret or something.

The War on Drugs Follows Me Home

Tanya and I literally stayed at the coca museum until just before my cab was to arrive at the hotel to go to the airport. At the very end, I decided to purchase some coca. I forked over just under $1 for an ounce (a high price, compared to what you pay on the street) and Tanya warned me that it might be confiscated by airport security or customs. I was going to buy more but I didn't after she said that. Others were taking their coca home in the form of tea (in tea bags) since that's all any of us were using it for anyway. Honestly, you'd have to be the world's dumbest drug smuggler to go all the way to Bolivia to bring back $1 of coca. With 1 oz of leaves, I could make about 1/100th of a gram of cocaine, if I was really stupid enough to bother (and to want it).

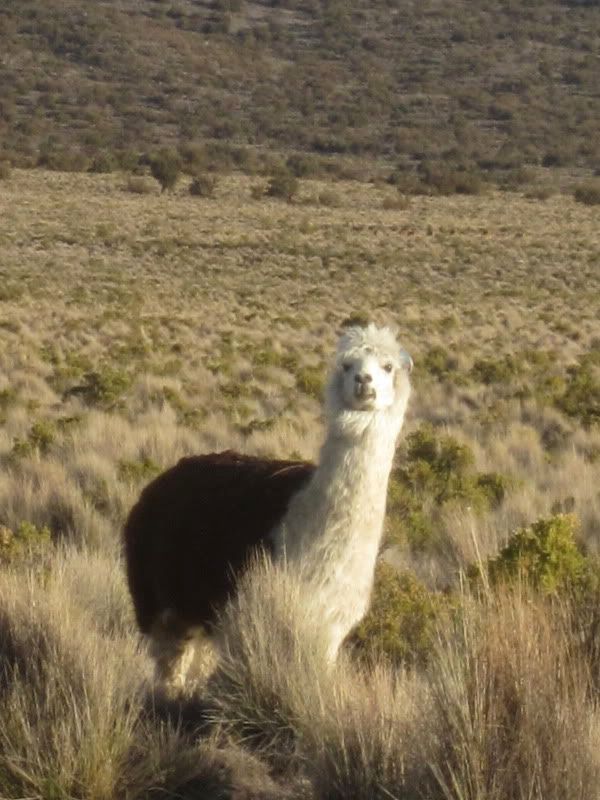

Just in case, I put my coca in between a bunch of alpaca sweaters, buried in one of my carry on bags. Not even thinking much about the coca, I bought as much coffee as I could afford at the airport, since it was the variety I had heard was the best in Bolivia and it cost far less than coffee in the U.S. I put that on the top of the same bag. This bag was searched - I'm not sure for what but I assume drugs - as I went through security in La Paz. I babbled on about the alpaca sweaters and how much I loved visiting various tourist sites, and the officer searching my bag decided there was nothing dangerous in there and sent me along. I heard later that others in our group had their coca taken away from them but were allowed to keep the tea that was in tea bags.

Another American who I met in the airport was also traveling through Lima to Mexico City, so we hung out together a bit. At the baggage claim in Mexico City, we stood together and waited. And waited. A few bags would come out, then the entire operation would stop. Then a few more bags, and a stop. My new friend said "I guess those are your American tax dollars at work." I looked through a glass window and saw a dog walking along all of the bags, sniffing them for drugs as he (or she) went. After the dog sniffed each batch, they were sent through on the carousel to the awaiting passengers. It was then that I remembered hearing that sometimes drug smugglers pack coffee with their drugs to throw off the dogs. Well, I packed coffee because I like coffee! I'm accidentally a very good

narcotraficante I guess.

The War on Drugs did not end there. In Tijuana, I had to wait in a line to have my luggage scanned one more time before leaving the baggage claim. Then, I went to the U.S. border and waited in a loooong line. When I got up to the front, the U.S. customs agent asked me what I was doing in Mexico. I told him I went to Bolivia. He said, "Drugs come from Bolivia." I told him that's not what I was doing there. He kept asking if I had something to declare, and I kept saying no. Was I sure? Yes, I was sure. Unless you want me to declare alpaca sweaters. Well, or coca. WHICH IS A TEA NOT A DRUG DAMMIT. I didn't declare the coca, and he let me through.

Thus, my coca made it home safe and I've been enjoying it as a tea ever since. I've shared some with friends as gifts, particularly folks who like hiking and need something for altitude sickness when hiking up Mt. Whitney (the tallest thing to hike that is relatively nearby... tall enough to make you sick). All in all, I'm disgusted by the drug war. For the amount of money they spend screwing over peasants, why can't they put that money into treatment for Americans and into prevention programs that work? There wouldn't be cocaine production if there wasn't cocaine demand. And, according to the museum, 50% of the demand in the world is from the U.S. If I were a Bolivian, I would be outraged. Why can't the Americans fix their own people if they want to stop the drug trade? Why do they have to go to South America to wipe out the coca crops of poor peasants?