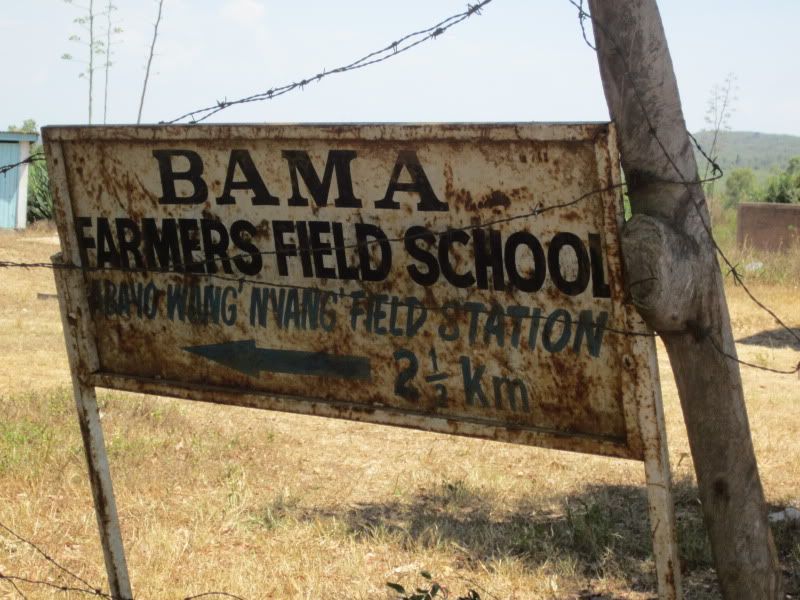

When we arrived at BAMA, it looked like nothing. A tiny building - that's it. My hosts, Amy and Malaki, were trying to call to see if anyone was there to show us around, but it seemed like the place was empty. I was ready to throw in the towel and leave.

BAMA

Eventually, an incredibly sweet woman came out to meet us. She brought a few chairs outside and we sat under the tree pictured above and talked. Then she showed us around.

BAMA is a community based organization [CBO] representing four communities. The name BAMA is an acronym made up of the first letter of the names of each of the communities. They do some work with Action Aid.

These communities were always very poor and had a terrible problem with African sleeping sickness and the tsetse fly. Many of the young people in these villages left and went to Lake Victoria since they couldn't make a living at home.

But the lake has a terribly high AIDS rate, and many of the young people who went there became infected with HIV/AIDS. HIV/AIDS takes out people in the prime of life - ages 15-49 - because 80% of transmission in Kenya is from unprotected (mostly heterosexual) sex. Often people already have children by the time they get infected, and when they die, the children are left with elderly grandparents or alone in child-headed households. There are several child-headed households in the communities BAMA serves.

Many diseases take out the very old and the very young. By taking out people in the 15-49 age group, AIDS is unique and causes unique problems. If many babies and toddlers are killed by malaria, the parents are still around, retaining knowledge about farming and having the physical ability to farm. But if the parents die and the children and elderly are left, the children often don't know how to farm yet, and neither the elderly nor the young have the capability to do the most difficult physical labor required in farming. Also, it puts a strain on the child's ability to go to school if that child must also work or grow food in order to eat every day.

So these communities formed BAMA to try to help their people make a living at home, to keep them from going to the lake and getting AIDS. The first thing the woman told us about was a cattle dip that they made. If you remember from my interview with Sidney, the Maasai man, he spoke about cattle dips too. They put pesticides in water and then have the cattle go in it to kill all of the ticks and bugs on them. The pesticide lasts for a week, and the cows must be dipped again seven days later.

Apparently, the exotic breeds are far more susceptible to Kenyan diseases than native Kenyan breeds, but I'm no expert in the tsetse fly and African sleeping sickness, so I don't know how susceptible local breeds are to that vs. exotic breeds. I have heard that the chemicals used in the dips are pretty toxic and that neem can work as an organic alternative. But a lot of development work revolves around cattle dips, and communities like BAMA feel that they need them.

If you recall, Sidney noted that during the 1990s, the government's veterinary services just collapsed. It turns out that was a result of Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs) imposed by the World Bank and the IMF. So the government used to offer free cattle dips, at least where Sidney lives, if not here in Bondo, and then the dips became privatized and services were no longer free. Sidney's community handled it by pooling their resources to create their own cooperative dip. That's basically what BAMA has done too.

Cattle dip, I think

BAMA also offers a food bank for locals who are in need. Now they just have some bags of maize, and last year they had sorghum as well. She said last year they had to give the sorghum to neighbors who were starving, and last season, only maize was planted.

Bags of maize in the food bank

They also run a pharmacy. The meds here are ones for immediate emergencies. It's not a full stock of everything under the sun.

Pharmacy

They are also promoting traditional vegetables and herbal medicines. Below, you see Crotalaria brevidens, which the Luo call mitoo. It's dried, and the woman said it tastes even more delicious this way. To cook it you can rehydrate it and cook it with milk. She said you need to cook it with milk, which is what I heard from several sources while in Bondo.

Mitoo

BAMA created a terrific little brochure of traditional vegetables and their medicinal properties. I've typed it out below. One caveat to this is that I've read a study that surveyed healers in this region and there was often little agreement among them about what cures what. So some of these medicinal properties might be true, and some of the plants might just have value as food but nothing more.

The brochure is a "popular version of a research done by Maseno University in collaboration with BAMA CBO and funded by Action Aid." It says "The community is advised to promote the production and consumption of local vegetables which had earlier neglected to get the micro nutrients most needed for boosting the immunity especially in the wake of the HIV/AIDS scourage)" [sic]

- Black nightshade (local name: osuga): treats diarrhea, eye infections, 'orianyancha' yellowing of eyes (jaundice), blood clotting

- Cats whiskers (akeyo): Anti HIV/AIDS, through immunity boosting, anti mosquitos, controls epileptic fits, anti fungal, increase libido & induces labour pain.

- Rattle pod (Mitoo): Treats boils, improves appetite, 'akuoda' stomach pains and swellings

- Amaranth (ododo): Treats anemia, adds strength

- Local name: Nyasigumba: Lowers cholesterol levels

- Local name: Atipa: Increases weight, skin infection and digestion

- Cowpeas (Boo): Leaf-extract treats skin infections, epilepsy, chest pain, and snake bite.

- Pumpkin (susa): Anti-malaria, control sugar levels in the body

- Milk thistle (Achak achak): Antibacterial, improves appetite, root extracts treats measles symptoms.

- Stinging nettle (Dindo): Treats arthritis and controls pests

- Water spinach (Obudo nyaduolo): Flower buds treat ring worms and sedative (makes you sleepy)

- Black eyed susan (Nyawend agwata): Crushed in fat and used as purgative (yomo ich)

- Traditional kale (Kandhira): Seeds used for treating stomach ache

- Ethiopian kale (Nyar nar achak achak): Sedative, and weight control

- Black jack (Onyiego): Crushed to water and treats malaria, boosts immunity

- Jews mallow (Apoth nyar uyotna): Appetite, digestion, and skin infections

- Local name: Awayo: Treats eyelids, ringworms, boils, and stomach troubles

- Cassava leaves (It marieba): Roots important in starch for gelling purposes

- Sweet potatoes (It rabuon): Leaf sap pusedas sedative and treats ringworm

- Hyacinth bean/Lablab bean (Okuro): Lowers blood pressure

- Malabar spinach (Obwanda, milare): Antifungal

- Local name: Nyar bungu odidi: headaches, colds, and anti-fungal

- Mung beans (leso riadore): Treat skin infection, epilepsy, chest pain, snake bite

- Local name: Bombwe: Treats abscesses and boils

- Local name: Oinglatiang: Treat any type of stomach ache and gastric ulcers

- Bitter leaves (Rayue): Has anti-tumor activity (anti cancer)

- Amaranth (osoyi): Anti-viral compoound has been isolated from the plant [Note: This is a different local name than the other listing of amaranth. There are multiple amaranth species within Kenya, although I don't know if these are two names that are both generic to amaranth, or two names representing two species.]

- Horse radish tree (moringa): Controls blood sugar, eases labor pain, antibacterial and immune boosters of sore throats

The other pages of the brochure explain why people should eat each vitamin, mineral, and macronutrient. Then it has a table showing nutrient contents of various local veggies. The woman showing us around said she didn't know about the plant mitoo before this project and now she eats it. She thinks it's delicious. As I asked her about how her work here changed her diet, she added "I'm also a widow." I did not ask because I didn't think it's polite, but if her husband died of AIDS, it's likely enough that she's infected too. She told me she farms and raises a dairy goat. The dairy goats are another BAMA project.

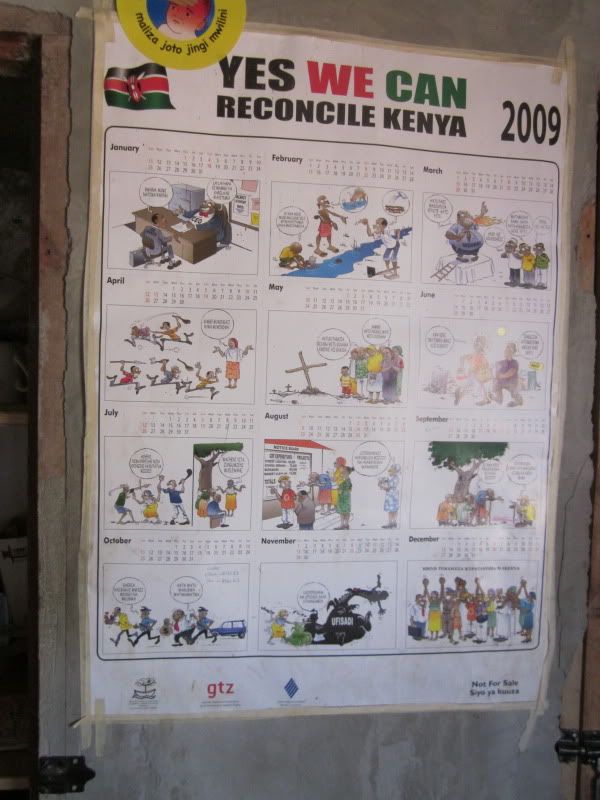

Think there might be a few Obama fans here?

Then we met the goats...

Obama has a dairy goat project. Traditional Kenyan goat breeds are almost entirely used for meat. There's been an effort to bring in German Alpine dairy goats to promote keeping goats for milk. BAMA will not sell anyone a dairy goat without training them first on how to care for the goat, but after training, you can buy a female goat that has one German Alpine parent and one local parent for 5000 shillings ($60). A goat with 75% German Alpine genes goes for 10,000 ($120) and a purebred German Alpine goes for 15,000-18,000 ($180-$216). That's for the females.

BAMA promotes "zero grazing," which basically means confining the animals and bringing the feed to them. It's a novel concept in Kenya. All of the goats they had are purebred German Alpine. The babies in the photos are three days old. The babies will stay here to nurse for two months before they can be sold.

The goats' "zero grazing" housing setup

They told us the amount of milk depends on their feed and management. Right now in the dry season, they are producing 4 liters a day with two milkings per day. These purebred goats must be "supplemented" with purchased feeds.

BAMA keeps a German Alpine buck on hand to mate with people's goats if people want their goats' offspring to have German Alpine genes. I asked whether some of the German Alpine goats died, and she said yes some did. It sounded like they concluded that when people are first starting to raise these dairy goats, they have more success with the 50/50 goats that are mixed with the local breed than with the German Alpines. When you mix the local breed with the German Alpine, you get more adaptation to local conditions, but less milk.

I heard mixed opinions on keeping purebred exotic breeds, or even animals with one local parent and one exotic breed parent while I was in Kenya. Organizations like BAMA and another one we visited called Care for the Earth promoted them. I met a man who worked for the Kenyan Dept of Veterinary Services who keeps all purebred animals, as well as a two others who kept one purebred cow each (a Friesian for milk in one case, and a beef cow in the other). But there's a risk and an expense to keeping such a high maintenance animal like these, even if you are going to get some extra milk from them. If you keep a 50/50 or 75/25 mix, the question is whether the increase in adaptation to local conditions outweighs the resulting decrease in milk you get from having a mixed breed. I don't have the answer to that question, but I am a skeptic of these efforts to push purebred animals, particularly if people are paying so much for one. I don't know what a local breed goat costs, but if a 50/50 Alpine mix costs half the price of a purebred Alpine, then that's already saying something.