Recall that the community we were visiting decided all together to go organic and adopt biointensive farming with the help of SARDI (Sustainable Ag & Rural Dev Initiative). The 15 farms each border a river so the farmers have as much water as they can carry - unless they have a water pump.

We left the farm of Waithera Kimotho and walked a short distance to the home and farm of Simon Kiarie. Like so many communities in the Global South, they didn't have roads - they have trails. After all, no one has a car.

Simon in front of his home

Simon is one of five brothers. His father had five acres and it was split among the brothers so that each now farms one acre. Simon began farming here in 1979. Simon says that the farms in this area are each one acre or less. Actually, Simon's wife Peris does the work on this farm because Simon was injured several years ago and now cannot handle anything beyond light work. They do not employ anyone else to work on the farm.

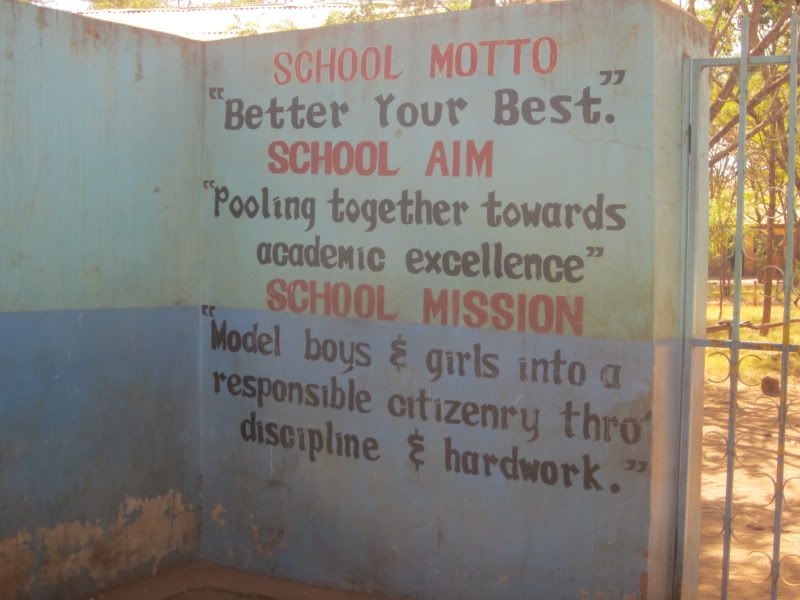

Simon and Peris had four children. They have two girls who are married, one boy who died, and one remaining son. Their son is in fifth grade, and his school costs 14,800 shillings ($178) per term. They had to sell their livestock to pay for his school.

When he began farming here, Simon used chemicals. But they stopped using chemicals two years ago. They were influenced to do so by a program they heard on the radio, and they decided to just give it a try. The chemicals were expensive, Peris said, and they didn't help them. "The fertilizer is very expensive and the product is not all that much," said Peris. "It hardens the soil and increases the salt," added Simon.

Simon and his wife impressed me with their sophistication. First Simon showed me his tissue culture bananas. Then he showed me an avocado tree that had two different varieties of avocado grafted onto it. He said he did the grafting himself.

Tissue culture bananas

Sweet potatoes

Avocados

He sells both the bananas and the sweet potatoes. He also grows amaranth, cassava, mangoes, papaya, coffee, maize, beans, onions, and cowpeas. The maize and beans are intercropped, and he does not grow enough to sell any. However, after switching to organic, they had enough extra maize to give some to their child's school to offset their tuition costs. They grow two maize crops per year. One is planted in March and harvested in August, and then they plant again in October.

Simon and Peris irrigate with water from the river but they have to carry it by hand because they do not have a pump.

HUGE cassava plant

Next door, Simon's brother has coffee trees that are loaded with unripe fruit. He is the sole member of this community who has refused to go organic, and he uses chemicals on his coffee. Kenyans don't really drink coffee - this is all for sale.

Simon also grows coffee, but he doesn't have as much fruit on his. His wife says she doesn't have enough manure for the coffee now so she won't get a harvest. And she says the chemicals you need are very expensive. It sounds like even though the rest of the farm is organic, the coffee might not be. Peris added that coffee needs enough water and when there is enough rain and she has enough manure, she harvests 1000 kg. Neither brother uses shade trees for their coffee at all.

Simon's brother's coffee - NOT organic.

Simon's coffee

I asked Simon about the difference once he switched to organic. He said "Once I began using manure, it grows big."

Papaya

Compost

Double dug field

The farm

Gravillea, a popular tree to grow in this area

A newly planted bed of cowpeas and onions.

During our visit, they were burning the remains of their last corn crop and said they would spread the ash on the field. Francis advised them to compost it instead of burning.

I tried to ask Peris about her yields back when she used chemicals. "Once we used fertilizer, we had to use other chemicals for spraying. Pesticides," she said. But she said she doesn't need to use that now. She just uses manure. I didn't get a very clear answer from her about yields but it sounded like the yields were determined by how much rain there is. She said she needs about 3 90 kg bags of maize to feed her family and she can usually produce that much on her farm, but if the rains fail, she won't get it.

She said, "There's not enough rain anymore... Before it was really proper rain. There was heavy rain early. By February, we get enough rain. March - up to... But this time, there is not enough rain." She wants a water pump. That would cost 40,000 shillings, or $480.

Another issue Peris brought up is that there is sometimes theft. People will come to the farm and steal her harvest.

We then took a walk from Simon's farm to see a few other farms along the river. We ended at Waithera's farm.

Black nightshade, a popular Kenyan crop. They eat the leaves. I tasted it and did not like it much.

Black nightshade ripe fruit

Black nightshade, flowering.

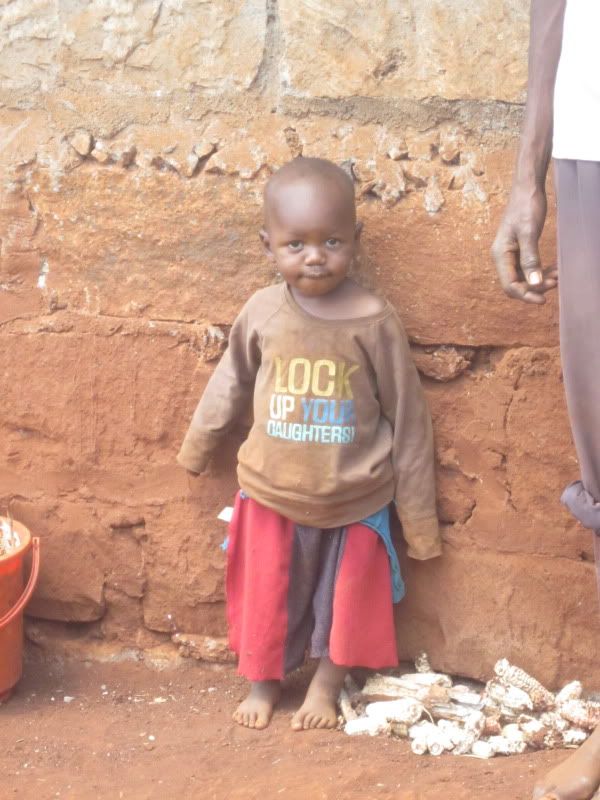

As we walked, a little boy named Wilson would tap me on the back occasionally and point out various plants. He was one of the neighbor's kids. Age 12. When we ended at Waithera's home, I took this picture of him:

We ended by taking a photo of everybody: