Our ninth day is difficult to sum up succinctly because we did many small, completely separate and different activities as we traveled from Rurrenabaque to La Paz to Oruro. This diary will cover the last part of our day, as we visited the community of Tomarapi, made a surprising (and disturbing) discovery showing the impacts of the climate crisis, and finally made our way to a small family-run hostel in Sajama National Park.

My trip was organized by Global Exchange and Food First. You can find out about future Food Sovereignty tours at the link.

After our earlier stops, we finally came to our destination: Sajama National Park, home of the highest forest in the world. Bolivia has 9 mountains taller than 6000m and we were near 3 of them (Sajama and 2 others). After starting our day under 300m above sea level, we were ending it at 4300m. (This was not a good idea, by the way, and a few members of our group were quite sick from it.)

Sajama

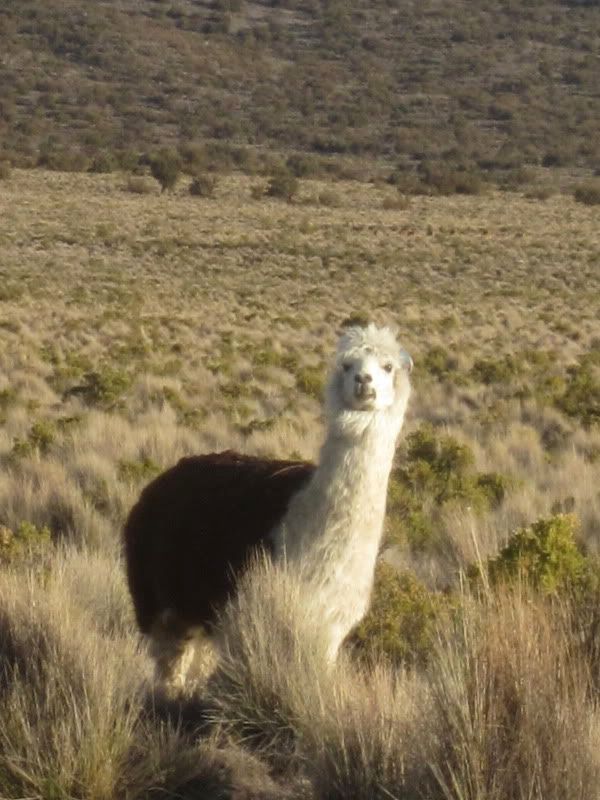

Sajama National Park is characterized by several different habitats: grasses, shrubs, and trees. There are also some salty areas where nothing grows. Altogether, the park has over 200 plant species. In addition to a number of birds, there are vicuñas, foxes, pumas, and viscachas (similar to hares). In the grassy areas, there is a bird called a tinamu that cannot fly very well. The area is also home to the Andean condor, an absolutely enormous bird with a wingspan that is among the largest in the world (up to 10.5 feet).

As you will be able to tell from the pictures below, the climate here is harsh. The winds are fierce and the temperatures are cold, particularly at night. During the day, it can be quite nice out, but even in the morning, around 6am, it was about 25F when we visited. Unlike the wetter part of the altiplano, this area does not get snow in the winter (the dry season). They get their snow during the summer, the wet season, because that is when they have the most humidity.

Trees

Sajama, rising above an area of shrubs

A shrub among grasses

Grasses - the tall, clumping grasses are prickly, and they can even stick you through your clothes

Some of the grasses grow close to the ground like cushions. This way they are protected from the wind and they can lock humidity inside of themselves. You can see our guide, Bolivian biologist Gabriel, with one of these plants below. One species of cushion-like plants, yareta, is now threatened because it grows only 1mm per year, but it makes an excellent fuel source. Yareta has been harvested for a long time as a fuel source for Bolivia's mines. Some of the individual plants are older than Jesus. You will see that they are very short in height, but surprisingly, they can have roots that are 2m to 5m deep.

A grass that resembles a cushion

Yareta (the bright green spots)

Teeny tiny white flowers (I swear they are there!)

Here, the agriculture mostly consists of Andean camelids: llamas and alpacas. Some people have sheep, and I also saw a few chickens and a donkey. The area is dotted with small corrals called estancias where shepherds put their herds at night. Sometimes the estancias are far from the shepherds homes, so they have small houses where the shepherds sleep as well. The corrals are made from stones, wood, or grasses. Some medicinal plants grow here, but (to my knowledge) no crops do.

After arriving in Sajama National Park, our first stop was a town called Tomarapi. They are an indigenous community that has survived by running an eco-tourism operation. We stopped to see a pretty church in the town, but instead of going inside, I used the opportunity to shop for the handmade alpaca hats, mittens, scarves, and more, made by the people of Tomarapi.

Tomarapi's church

Tomarapi's Eco-lodge

Tomarapi's Eco-lodge

Tomarapi's Eco-lodge

A view of Sajama from Tomarapi

After leaving Tomarapi, we continued on our way. Gabriel had been promising me lots of flamingoes and even some vicuñas. All of a sudden, we came upon a dried up lake. Gabriel was shocked. The lake, Laguna Huayñacota, has never been dried before. We checked later, asking our hostess for the night about it. She said the lake normally shrinks in the summer but it never disappears. It's been dry for 2 months now.

Gabriel worried about the fish that used to live in that lake. This part of the Andes was once under water (a long time ago) and when the Andes rose, the fish rose with them, evolving in that lake as they went. Now the fish were gone. Needless to say, there were no flamingos living there, or vicuñas drinking the water.

Laguna Huayñacota

Earlier in the day, we had seen another pond that was also drying up, which I snapped a picture of as evidence of the climate crisis.

A pond we passed earlier in the day that now resembled more of a puddle

The climate crisis is hitting Bolivia in a number of very clear and alarming ways. On many mountains, glaciers are receding, in response to changes in precipitation, temperature, solar radiation, cloudiness, humidity, and climactic events like El Niño. For example, the glacier on a mountain called Chacaltaya was considerable in size in 1994, tiny in 2005, and all but gone in 2009. This is having an impact on Bolivia's reservoirs as well, which are noticeably receding.

The changing climate also helps pests enter new areas, such as weevil larva that like to eat the Andean staple, potatoes. Late blight, which devastates potatoes, is an example of a disease that is moving into new areas with the changing climate.

Climate change has brought both droughts and floods in recent years, and the rains come later than they did historically. In some parts of Bolivia, desertification is a problem. Many farmers use bio-indicators to tell them when to plant or harvest, etc. This means they might plant when a certain bird arrives, or a lizard appears, or a specific tree flowers, etc. But now, with the changing climate, these bio-indicators are no longer reliable.

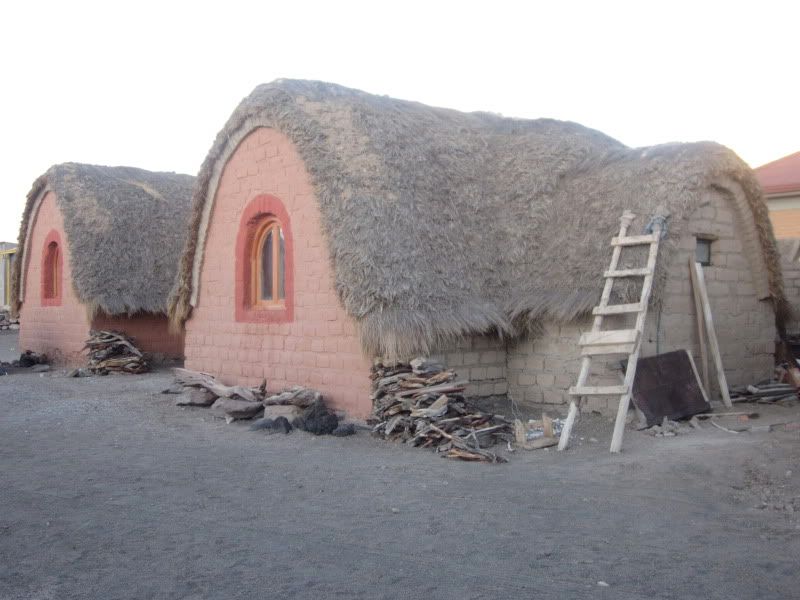

We continued driving around Sajama, past the dried up lake, finally arriving at a hostel where we would spend the night. In this area, many families operate their own small, bed and breakfast style lodgings, and we were staying at one. The family's house was attached to the dining room, and we were invited to watch our hostess cook dinner (and help, if we wished).

Half of our group was sick from the altitude and various other ailments, but several of us crammed into the kitchen. A major perk of hanging out in the kitchen was its warmth. I bundled up in layers and warm clothes, but it was COLD out. In addition to the eco-lodge, the family had a herd of llamas... one of whom was our dinner.

A lovely view of Sajama at sunset

A "laka uta," literally "house of mud." Each of these little structures contained one room and bathroom with two twin beds.

A pile of firewood - look at how twisted the logs are!

Our hostess, cooking dinner and wearing a hat indoors (it's so cold!!!)

An ax, not a normal kitchen tool in my world, but I guess it is here

Trimming the meat

Llama meat

Llama, cooking

Browned llama meat

A lovely Andean table

Corn soup

Potatoes, llama, and quinoa

No comments:

Post a Comment