If reading about the people I've visited inspires you to help, you can donate to the Center for Farmworker Families. Every penny given goes directly to these families for clothes, shoes, food, school supplies, and more.

Our second day of rancho visits began by gathering all of the necessary supplies: the pinata, watermelon, and a few suitcases of goodies. Like the day before, at 1pm, the cops showed up to drive us to the rancho. This time they brought both their truck and their van. Our pinata and watermelon, etc, rode in the truck. We rode in the van. That is, until we reached a dirt road near the house we were visiting. It had been raining and the road was too muddy for the van to pass. The truck could make it. Everyone got out of the van, and some began to walk. I was going to walk but fell promptly on my behind, and then got in the back of the truck.

Pinata #2

The cakes and watermelon

We pulled up in front of a large cornfield that was proudly advertised as corn grown from Monsanto's Asgrow brand hybrid seeds. From there, we got out and walked about a block past the cornfield, to the home of a woman I will call Lupe.

Asgrow (Monsanto) hybrid seeds

A view of the milpa (cornfield)

Lupe is in her late '40s and she has five kids, ages 23, 18, 15, 8, and 6, probably from different fathers. Her 23 year old is a woman who I will call Raquel, and Raquel has three girls between the ages of 6 and 2, two from one father, and the third from her current boyfriend. Raquel lives with her boyfriend. All in all, between Lupe's children, grandchildren, and neighbors, we were immediately confronted with a swarm of very cute little girls.

Lupe's house

Another view of the house. Until this past year, Lupe had a dirt floor. The federal government gave her a cement floor this past year.

A view of the yard. Many people ride bikes around here.

Some squash in the yard

The milpa (cornfield)

Lupe had told everyone in her rancho to show up around 3pm, and we arrived a little early. While we were waiting, Ann asked her about the frogs. Lupe has previously said that all of the frogs in the area are dead because of the agrochemicals. We took a look at the nearby pond. We saw no frogs, but lots of mosquito larvae - a bad sign that there are no frogs around to eat them.

One woman who came with her sons told us that she was having a hard time keeping them in school. Already her oldest had to drop out to work in a shoe factory in Cuquio. The others are still in school but she fears she won't be able to afford for them to continue.

Before too long, a crowd of women and children gathered, with a few men among them as well. And thus began the festivities - the pinata, distribution of cake, toys, shoes, clothes, school supplies, and toothbrushes and toothpaste.

The girls, comparing their new toys

With the help of some older boys, I took stock of the various fruit trees in the yard: guava, orange, mandarin, lemon, lime, banana, grapefruit, peach, apple, sapote, pomegranate, guamúchil, and formerly a mango tree that is now dead. I'm pretty sure I saw more than one guava tree. The boys also pointed out that Lupe grows chamomile and mint.

Another member of my group joined me and we began chatting with the boys. They were all still in school, middle school and high school. We asked what they wanted to do when they grew up. One said he wanted to be a professional soccer player, one said he wanted to be a doctor, and the third said he wanted to go to the U.S. His parents are already over there, he said, and he has papers to legally go back whenever he wants. However, he started school here so he will finish here before heading north.

When the kids were done receiving their various presents, we asked Lupe to tell us about her life. This was perhaps a mistake, and certainly a low point of the trip, because as she spoke about her life, Lupe got sadder and more despondent.

Lupe lives with her children, without a husband or boyfriend. Ann suspects she may be outcast from the majority of her family because she's had children out of wedlock, but never asked because Lupe gets so sad any time she speaks about her own life.

Lupe told us that she is one of 12 children. Of the 12, three still live in this area. Some are in Guadalajara, some are in the north of Mexico, and some are in the U.S. She's lost touch with the ones in the U.S.

We first asked about her hopes for her kids. She said she wants them to study to have a better life. Her youngest will start first grade this year, her eight-year-old is starting third grade, and her 15-year-old is in middle school. Unfortunately, she did not have the money to pay for her oldest to finish school, and he is now working in the shoe factory in Cuquio instead of attending school. When asked what she wanted for her own life, she said she only wanted to support her kids any way she can so they can continue to learn.

Then we asked what her life was like. "I'm a housewife," she answered. "So, you cook, you clean?" we asked. "Yes, and I wash the clothes," she said. Her laundry was hanging in the yard on a laundry line.

We asked how often she leaves the rancho. She said she gets into Cuquio every few months but she can't remember the last time she went to Guadalajara. We found out later that she's part of the "Oportunidades" program, which seems to be a sort of welfare program that provides 500 to 1000 pesos to poor people in this area every other month. Lupe gets 740 pesos every two months, and she has to come to Cuquio in order to receive it.

She told us she eats corn tortillas and beans for each meal, and she has eggs every day. She grows enough corn and her hens produce enough eggs, but in the bad years she has to buy beans because she can't grow enough. Once or twice a month, she eats meat. Typically, she'll buy chicken, unless she has enough chickens that she can slaughter one and eat it.

In good years, she can sell some of her corn. She takes it to Cuquio and sells it for 2 pesos per kg (about $.20 per kg). The most she's ever sold was 400kg of corn for 800 pesos ($80). She doesn't know yet how much she will grow yet this year.

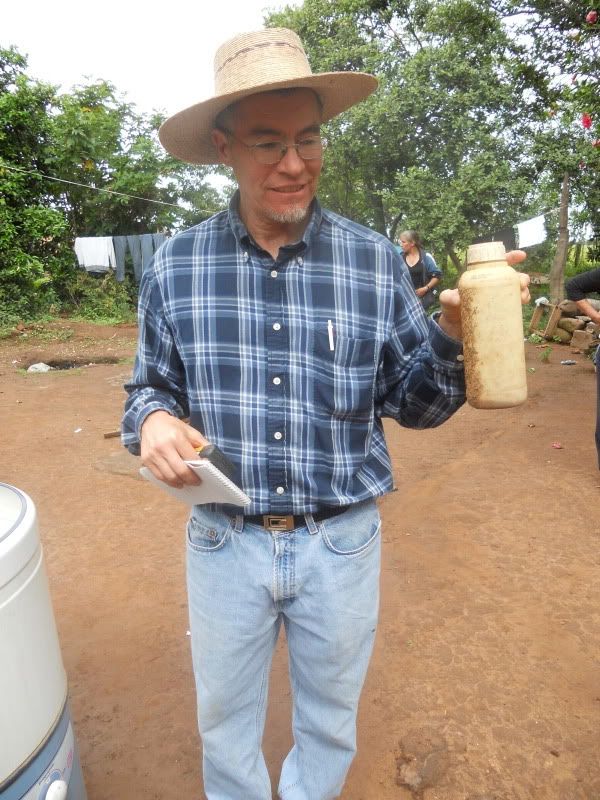

Her brother helps her with her milpa (cornfield). He purchases hybrid corn and agrochemicals and rents a tractor too. The entire family - including the kids - participates in the farm labor. Her older boys apply the pesticides using a backpack with a pump. They wear no protective gear whatsoever. She wants her sons to put the chemicals away so the kids don't play with it because it's so toxic, but sometimes the kids do play with it. Typically they burn the bottles to get rid of them. However, while we were talking to her, someone found one unlabeled bottle lying in the yard with chemicals still in it.

A close-up of the cornfield, tilled by the tractor and treated with herbicides. Notice the bare ground as well as the squash plant in the middle of the picture.

Gus, playing with agrochemicals

When asked how the hybrid seeds and agrochemicals have changed her life, she says that growing their food is less work now. Even though she and her brother have converted to a more industrialized way of growing corn, they still interplant beans and squash in their cornfields. As Lupe got more discouraged throughout the conversation, her niece began to answer the questions for her. The niece said that the agrochemicals are removing quite a few natural plants from the area, and added that there was a talk at the school about the effects of chemicals on the environment.

We asked her what the most difficult part of her life is. She replied that paying for school for the kids was the hardest for her. She said her family eats very poorly but they have their tortillas and beans. Getting money for school supplies, fees, shoes, and uniforms is the most difficult. Every year the schools raise their fees. She wanted her oldest to finish school but there wasn't the money. (It costs about US$100 per year for a child to attend high school here.) Right now, the high school is trying to raise 35,000 pesos ($3,500) to buy a computer for each student to use while at school.

The biggest loser of our questions was when someone asked what Lupe would say if she could speak to the President of Mexico. Lupe looked totally stumped and just completely in despair, as if the President of Mexico would never have anything to do with her life and her struggles getting enough to eat and putting her kids through school.

While Lupe spoke, a very noisy chicken decided to lay an egg in the flower pot

Lupe's closest friend is her oldest daughter, Raquel. When we left, we gave Raquel a ride home and made arrangements to visit her the following week. Raquel lives in another nearby village with her boyfriend and at least one of her daughters (the daughter she had with her boyfriend). I heard from someone that her boyfriend doesn't want kids with dark skin and dark hair, so Raquel leaves her oldest two kids with Lupe most of the time. I don't know how much truth there is to that. When we gave Raquel a ride home, she only brought her youngest child with her. When we returned, several days later, she had all three children.

No comments:

Post a Comment