This is a diary that I have been both anticipating and dreading, because I swore that when I wrote it, I would commit to giving up sugar for a month, with minimal cheating by substituting honey and maple syrup. You'll see why as you take a look at Santa Cruz's industrial agriculture below.

Our trip through the industrial ag region of Santa Cruz was depressing. We weren't able to visit any large soybean producers or any other large scale producers either for that matter.

For our look at "irresponsible" production, we had to be content with what we could see from the bus window, and what our guides from PROBIOMA told us. I picked up a book on soy production in Bolivia, so at some point in the future I will write up what I learn in that book.

Santa Cruz was not very well populated until a push for colonization of Bolivia's eastern lowlands began after the 1952 revolution. The wealthy and well-connected got huge landholdings here, but many peasants came from the highlands hoping to get some land here too. The majority of people here moved here from somewhere else, or else their families did before they were born.

In Santa Cruz, a "smallholder" is one with 20 hectares of less. The average landholding of a large producer around here is something like 16,000 hectares (nearly 40,000 acres). There was a successful referendum that limited landholdings to 5000 hectares, but it was not retroactive. Also notable: 70% of land in Santa Cruz does not have a legal title.

We often saw enormous mounds, which are anthills large enough that you could comfortably sit on them, were it not for the ants. Ants like open spaces and poor soils, which is what there is a lot of here in this area that used to be forest. The ant hills are a sign of soil degradation.

This area is almost entirely deforested.

Hello, monoculture

As we drove, we saw fields and fields of monocultures on both sides of the road, interrupted now and again by billboards or shops for agrochemicals, processing plants, and a house or tree or two here and there. It was terribly dusty and every vehicle would kick up enormous clouds of dirt. Here's a shot I took of one of the processing plants we passed - a soy processing plant, I believe:

Processing plant

Honestly, what made an impression on me even more than soy was sugar. Soy is something I avoid when possible. Even most of the animal products I consume come from animals that did not eat soy, although it's very possible that the cows that make the organic milk I drink get some soy in addition to the grass they eat. But sugar, on the other hand... oh man do I eat sugar. And now that there are genetically engineered beets on the market, the sugar I eat is cane sugar.

We passed field after field of sugarcane. I did not take pictures because it's boring and not worth it. I've taken pictures of sugarcane before, in the Philippines. And if you've seen one field of sugarcane, you've seen 'em all. Then we came to a sugar processing plant. It STUNK. Bad. Here's a photo of the enormous area where the trucks come to drop off their loads of sugarcane:

Trucks carrying sugarcane

More trucks carrying sugarcane

Truck carrying sugarcane

These pictures were taken during a low traffic time of day. Later, we passed this spot again when there was a full-fledged sugarcane truck traffic jam. Truck after truck after truck, full of burnt cane. They burn the fields to get rid of all of the leaves, making it easier to harvest the cane. Burning is bad in a number of ways. When they do the burning, there are emissions of gasses, and sometimes all of the nearby homes are covered with smoke. But the burning is also very harmful to the soil.

In the past, there was a push for self-sufficiency in sugar and rice in Bolivia. These days, there's a resurgence in sugar production, and now sugar is replacing other crops like soy, corn, wheat, and even some ranchland. The area we were passing through used to grow wheat in the winter and soy in the summer, but now it was growing sugarcane.

In March of 2011, there was a sugar shortage and the price went up. The government responded by restricting exports of sugar. Producers and processors responded to that by turning the sugar into ethanol and exporting it that way.

Sugar processing plants only pay US$50 per tonne of cane, but only if the cane has 12% sucrose. For every percent less than 12% of sucrose, the producer gets less money for the sugarcane. It costs $800 per hectare to plant sugarcane, and that must be done every 5 years because it's a perennial. It yields about 60 tonnes per hectare, or US$3000 per hectare if it has 12% sucrose. Sugarcane is harvested annually.

The processing plant, as I said before, STUNK. It was impossible to drive past it without wondering about the overpowering smell. The plant is a source of air pollution, but it also produces effluent because it uses a lot of water. In addition to all of the water used, the plant also uses chemicals to whiten the sugar. The effluent from the plant is very contaminated, and it sits around in oxidation pools, which is what caused the smell. When it rains, the pools overflow, resulting in fish kills. The plants are powered by burning bagasse, which is the term for sugarcane after the juice containing the sugar has been extracted.

In addition to sugarcane, I also asked about a few other crops. Our guide told us that farmers would spend $350 to plant a hectare of soy, yield 2 tonnes per hectare, and sell the soy for about US$400/tonne. That means each year a farmer would net about $450 per hectare, less any interest paid on loans. For corn, a farmer would spend $280 to plant each hectare, yield about 35 quintals, and sell them for 90 Bolivianos apiece. That equals 3150 Bolivianos (US$455) per hectare (gross), netting the farmer $175 per hectare.

As we drove, we saw one man spraying pesticide. We could smell it inside our bus, and the man was wearing no protective clothing whatsoever. The most popular herbicides around here are glyphosate (Roundup), 2,4-D, paraquat, and atrazine. Popular insecticides are cypermethrin, methamidophos (banned in the US), chlorpyrifos, endosulfan (which is banned in Bolivia but people use it anyway), aldrin, dieldrin, and endrin. Many of these are highly toxic.

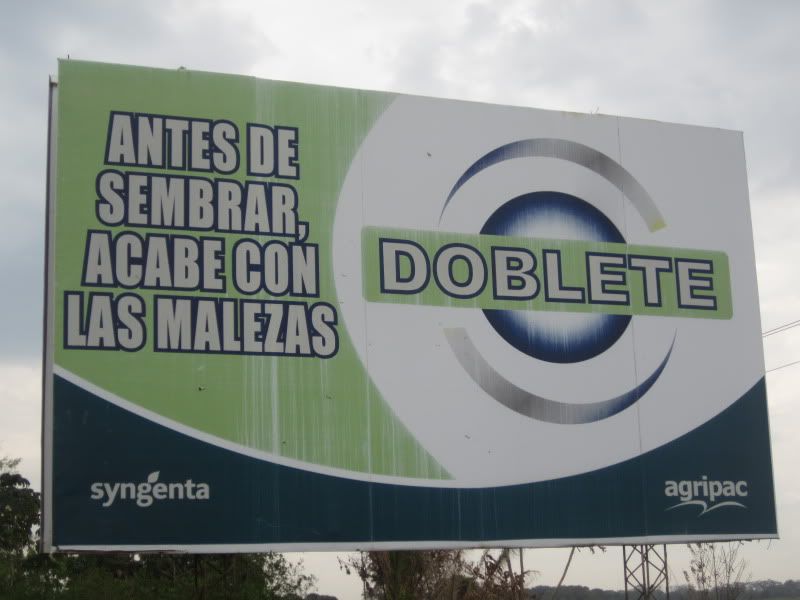

The other major site we saw were pesticide ads:

"Before planting, kill weeds"

Syngenta's Bolivia site is under construction, but in Mexico, Doblete Super is made from Paraquat and Diquat. In other words: VERY TOXIC.

Our friend Arysta Lifescience, the makers of methyl iodide, with their slogan "Harmony in growth"

I made a list of products I saw advertised:

Dow

Herbicides:

- Panzer Gold (glyphosate)

- Galant HL (Haloxyfop-P-methyl)

- Starane Xtra (Fluroxypyr 1-methylheptyl ester)

- Clincher (Cyhalofop butyl)

- Spider (Diclosulam)

- Combo (Picloram Potassium Salt and Metsulfuron-methyl)

Insecticides:

- Tracer (Spinosad (A & D)

- Lorsban (Chlorpyrifos)

- Exalt (Spinetoram)

Other:

- Uptake (A spray additive to improve the spreading and wetting of herbicides on plant surfaces)

- DAS-5000 (Hybrid sorghum seed)

BASF

Insecticides:

- Imunit (a mix of Cypermethrin, alpha and Teflubenzuron)

- Nomolt (Teflubenzuron)

Fungicides:

- Acronis (a mix of Pyraclostrobin and thiophanate-methyl)

- Opera (Pyraclostrobin)

- Allegro (Kresoxim-methyl)

Fertilizer:

Nitrogen fertilizer

Syngenta

Insecticide

- Engeo - A mix of thiamethoxam (a neonicotinoid) and Lambda-cyhalothrin

- Curyom (Profenofos - very toxic - and Lufenuron)

Herbicide

- Doblete (paraquat and diquat)

Bayer Cropscience

- Larvin (Thiodicarb - very toxic)

Other Companies

- Genesis fungicide by AgroBolivia (Azoystrobin and Cyproconazole)

- Orius fungicide by Mana Crop Protection (Tebuconazole)

- BIOGAL - a biological control by PRIOBIOMA!

Other Fertilizer Brands

Nutripak fertilizer

Misti fertilizer

Borpak fertilizer

Croplift (by Yara)