This diary covers their presentation on their work, as well as an outrageous story that cleared up the truth about the organization we had previously visited, Friends of Nature Foundation.

The director of PROBIOMA, Miguel, welcomed us. He said we were in a center for biotechnology and biodiversity. It is a training center in biocontrol, agroecology, land management, and monitoring of mega-development projects like mining and agrofuels. Here, they train farmers in agroecology. They also have a lab here where they produce microorganisms for use in biocontrols. They also have two factories that produce organic fertilizers and mineral fertilizers. PROBIOMA is an NGO, but they have created a company for producing and marketing biocontrol. They are the biggest enterprise in Bolivia of production of biological control resources for widespread use. Biological control means, for example, using ladybugs to eat aphids or using predatory mites to control pest species mites.

In case you wonder what he means about "biotechnology," here is what they think about GMOs:

"GMOs and the Food Security and Food Sovereignty Situation in Bolivia"

A close-up of the photo

After some introductions, Miguel began his presentation. These are his words, as best as I can transcribe them:

PROBIOMA has been around for 21 years. They work in agroecology and what they refer to as "biotechnology" - essentially biocontrols, but not GMOs. Their mission is to contribute to national development through research and innovation at the level of local, sovereign, and sustainable use of natural resources. Bolivia is considered one of the eight most biologically diverse countries in the world. Paradoxically, it is also among the last place countries in development indicators. This is why they think it's important to promote sustainable development.

PROBIOMA works with quinoa in the Altiplano, in the valley regions, and in the tropics (the lowlands). They work to support organic production of fruits and vegetables doing field experiments, planning production, training, and following up. They also work in other areas with the responsible management of large scale production for crops such as soy, maize, wheat, and quinoa. They support GMO-free production. They also work with saving native seeds and certification of GMO-free seeds.

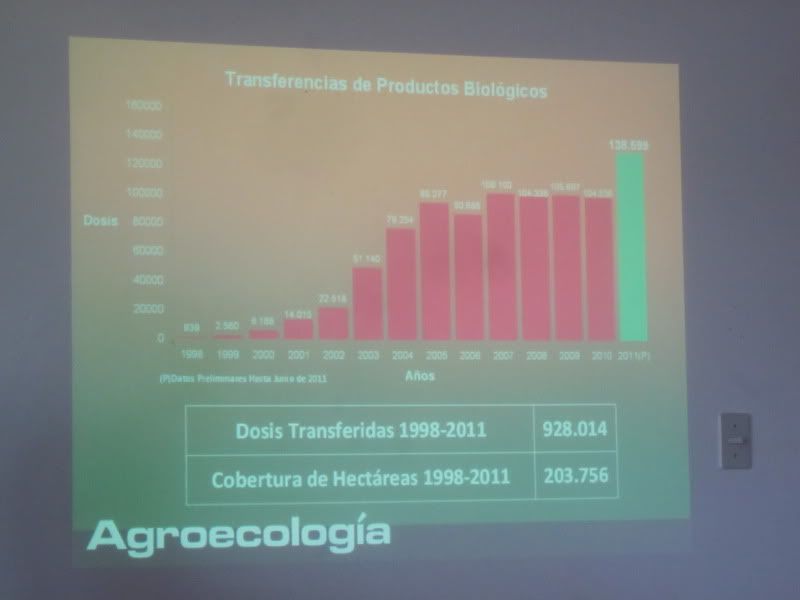

The technology and the resources they produce here for biological control are diffused and transferred to crops all over the country. For example, they are used on cacao, citrus, quinoa, Brazil nuts, fruits, and vegetables. In 1998 they received official recognition to transfer and commercialize their biological control products to the rest of the country. This was a biosafety certification. They increased our production - in 1998, they produced 939 doses of microorganisms for biological control to present day where they produced over 130,000 doses.

Graph showing the increase over time in doses of biological control microorganisms produced and sold.

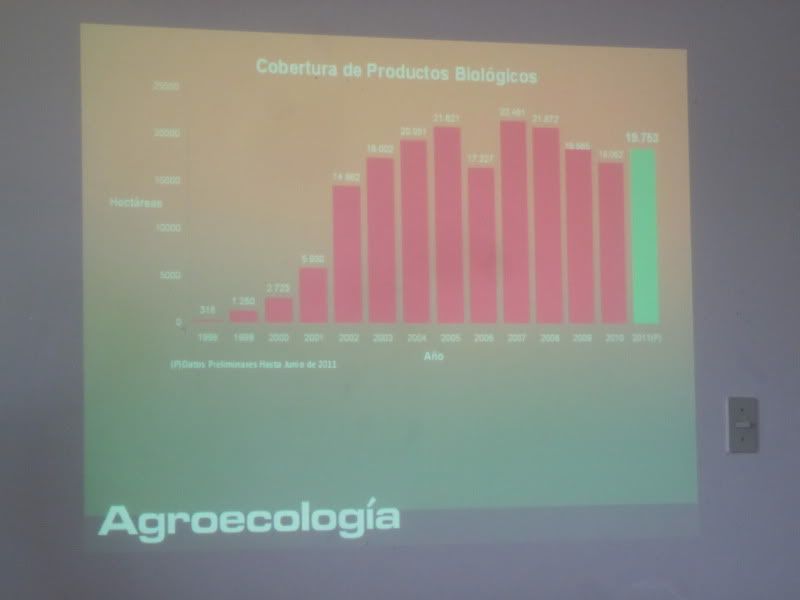

Graph showing hectares covered over time in biological control microorganisms.

This project actually began with a group of seven local peasant women who wanted to use this method, biological control, in their kitchen gardens. They always have these women very close in their hearts. They launched this project in opposition to their husbands, who thought it was a waste of their time. There was a kind of tipping point in 2002 when producers saw that this is a technology that is cheap, easy, safe, and improves their production. PROBIOMA began in 1998 with 318 hectares covered by their products and reached a high point in 2005 of 22,000 ha. It dropped in 2006 because of widespread droughts and floods, but it has gone up since then to almost 20,000 hectares thus far in 2011.

Over time, their products have covered over 200,000 hectares. That number yields about half a million metric tons of food with a value of about 2.5 million Bolivianos (over US$350,000). That's half a million tons of food being produced ecologically that is also being consumed. It represents the reduction of 250,000 liters of agrochemicals. Miguel thinks there is pretty much a 100% retention rate of their customers because the cost of PROBIOMA's products are so much lower than agrochemicals that people don't go back to them.

PROBIOMA's goal is to convert vegetable production to organic production. So they go to a farmer and show them the benefits of organic production and present their biological controls. So let's say a farmer grows tomatoes. They use biological controls, save money on the cost production, keep selling to the same markets as before for the same prices as before, but increase profits because they saved money on the cost of production. What PROBIOMA says they do not get involved in is the production of niche products that are more expensive in the marketplace because they want to democratize the production and consumption of organic products. What they do want is a situation like in the U.S. where organics have premium prices.

85% of what is produced with PROBIOMA's products goes to regular markets, not niche markets. Only 15% of production goes to certified organic niche markets. They see it more important to devote resources to the regular markets. There's really no state or government organic certification in Bolivia so if you want certification you need to go to international certification agencies that are very expensive and out of reach of the average producer.

Miguel showed us an example of one of their products, a bottle of a substance that protects seeds. The producer would then mix it with water and spray it. A larger bottle he showed us contained enough to cover half a ton of seeds or 20 hectares.

PROBIOMA's product lines are as follows:

- TRICODAMP: biological fungicide, bioregulator of phytopathogenic fungi.

- PROBIOBASS biological insecticide, bioregulator of pest insects.

- BIOSULFOCAL: fungicide and acaricide (mite and tick killer)

- PROBIOVERT: biological fungicide, bioregulator of pest insects and phytopathogenic fungi.

- PROBIONE: biologicla insecticide, biological regulator of pest insects.

- PROBIOME: biological insecticide, biological regulator of pest insects.

- BIOGAL: Organic foliar amendment

- BIOFRUT: natural lure or bait for flies

As you can see, these are branded and marketed products, reminiscent of how conventional agrochemicals are branded and marketed.

In political interventions, they monitor large scale development projects like large scale highways like the IIRSA project, of which the TIPNIS highway was to be a part. They have done a lot of work on the issue of road construction and gas pipelines. They give a lot of information to groups and social movements as well as the media to promote a better understanding on, for example, what it means for a forest to have a road go through it. They work with local communities in Chiquitania on the impacts of these projects.

At this point, he told us why PROBIOMA and FAN (Friends of Nature) do not get along. It has to do with a previous pipeline project by Enron and Shell that was to go through Chiquitania, the large, tropical dry forest in Santa Cruz department that is inhabited by the indigenous.

When Enron and Shell proposed the pipeline between Bolivia and Brazil, from Santa Cruz to Sao Paolo, PROBIOMA was monitoring the actions of the oil companies. The World Bank, the Inter-American Development Bank, and Andean Development Bank all supported the pipeline. The pipeline would cross the Chiquitania dry tropical forest, the last virgin dry tropical forest left in the world. With the CIDOB (Confederation of Indigenous People of Bolivia), Organización Indígena Chiquitania (Chiquitania Indigenous Organization, OICH), and the Coordinadora de Pueblos Etnicos de Santa Cruz (Organization of Ethnic Peoples of Santa Cruz, CPESC), PROBIOMA proposed that the gas pipeline go around the forest.

Shell and Enron requested a $200 million loan for the project, which I believe they requested from the Export-Import Bank. A coordinator from PROBIOMA went to Washington to protest this, along with indigenous leaders. The bank said they would not give the loan unless Shell and Enron could demonstrate it could be done in a sustainable way.

During this process, FAN (Fundación Amigos de la Naturaleza), World Wildlife Fund, the Missouri Botanical Garden, the World Conservation Society, and Fundación Amigos del Museo de Historia Natural Noel Kempff Mercado created a consortium to dialogue with the oil companies. The enviro groups agreed to take $1 million for a study to certify that the pipeline would not harm the forest, on the condition that if they did, they would found the Foundation for the Conservation of the Chiquitania Forest (Fundación para la Conservación del Bosque Chiquitano, FCBC) with a $20 million contribution from the oil companies. So the pipeline was built.

Because of international pressure, WWF withdrew from the consortium but FCBC continues. However, because of this, all of the member organizations of FCBC were expelled from the region by CIDOB, the indigenous organization. These organizations also lost a lot of credibility in Bolivia. And PROBIOMA continued to work in these regions and continued to work with the indigenous groups, who know they can trust PROBIOMA because of this experience.

The pipeline began in 1999 and was finished in 2002. Then it sat dormant for five years without being used. The impacts on the forest include traffic, land speculation around the area, illegal logging, sexual harassment and rapes in indigenous communities by workers and new people coming in, contamination of lakes and rivers, narcotrafficking, illegal hunting of wild animals, increased colonization of these areas and settlements by Andean people who come to the lowlands for its plentiful land, and more planting of monoculture soy cultivation.

No comments:

Post a Comment