"Model Farm: Managed with criteria of social and environmental responsibility. Proprietor: Francisco Gonzales. Supported and certified by PROBIOMA."

The farm we visited was owned by a man named Francisco. His idea for his 16-hectare farm is to "do something totally different" from the monoculture soy around him. Previously, they were growing soy, corn, potato, and sunflowers here. Like so many in Santa Cruz, Francisco was a highlander who came to the lowlands looking for land. And he was lucky. He met and fell in love with his wife, whose family had come from Potosi years before - also looking for land. This land was in her family.

Francisco with a beet

A view of the farm, including its two buildings.

As you can see in the photos below, the farm was anything but a monoculture. The farm had two small buildings, each containing just one room. One seemed to be a bedroom, the other a kitchen. These might be the home of Francisco and his wife, but I think it's likely they have a home elsewhere and just use these buildings for cooking and sleeping when they are at the farm.

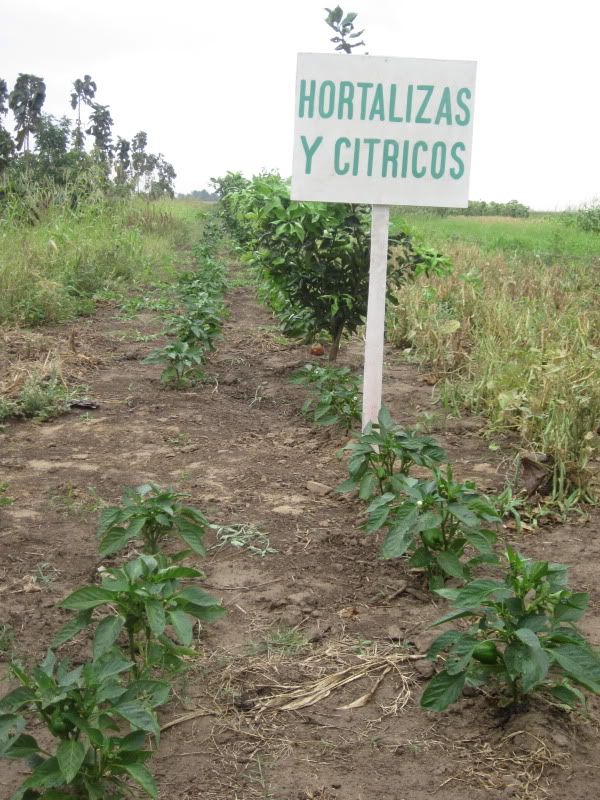

Francisco grows citrus trees, and just about every vegetable under the sun - potatoes, beets, peas, eggplant, squash, you name it. He also grows sunflowers, corn, and wheat. As you can see, he does not intercrop. He plants in long, straight rows of single crops. However, he has so much variety that no crop is very far from several other plant species all around it.

Potatoes

Citrus and Peppers

Beans

Onions

Cilantro

Squash

Eggplant

Wheat

Wheat and corn

Tractor... you don't grow wheat and corn like that by hand.

Beet

Sunflowers

Francisco told us a funny story about his neighbor. At first, when he began farming using organic methods with a polyculture, his neighbor got mad at him for growing sunflowers. The neighbor came over to complain that Francisco's sunflowers would cross-pollinate his. However, when he got to Francisco's farm and saw the quality of Francisco's sunflowers, he asked Francisco to grow sunflowers for him and sell them back to him.

He says that his neighbors have come around to ask questions a lot. They want to know what he's doing, where he gets his plants, and why he is doing this. He thinks they are curious and that they might switch to farming like he does if he can prove that he is financially successful over time.

At the front of his property (along the road), Francisco grows a number of trees, like mahogany and teak. While these are valuable as lumber of course, Francisco grows them for a different reason. His 16 hectares are in the shape of a long rectangle. Perhaps two thirds of the way across his land, he left a patch of natural forest. Beyond it, there are two hectares that sit in between two such patches of forest, which act like windbreaks. Francisco says that no matter what he grows, the land between the forest areas always yields higher. So he is attempting to create a similar sort of windbreak for the rest of his land by planting these lumber species in the front.

Trees

Trees

Trees

Close-up of one of the trees

After our tour, we went back to the house for our lunch. Don Francisco's wife prepared a traditional style lunch for us, a delicious soup made from one of her chickens.

House

Chickens... one of these guys became lunch.

Francisco's wife preparing lunch

After we ate, Francisco asked if we'd like to see his patch of jungle. Of course we would! As we walked over there, he asked me if it was true that the U.S. has no monkeys. Yes, I said. And, he continued, is it true that the U.S. doesn't have trees? No, I told him, That's not true. We walked a long way across bare soil that had been prepared for planting, or perhaps just planted. As we walked, he pointed out a few trees that he left standing for one reason or another. I think they were important species.

Bare field prepared for planting, with a tree

Another tree Francisco chose to leave standing.

A look at the jungle as we approached it.

Jungle

Once in the jungle, I was delighted to see a passionflower I had been looking for, a pachío.

Pachío, a wild passionflower that produces edible fruit

Another view of the pachío.

Another view of the pachío.

Then, all of a sudden, we saw a little monkey in a motacú palm! He scurried away quickly, before anyone could get a picture. We watched the tree for a little while but he did not show his face again.

I saw a monkey! He's right up there, in that tree! (Just hiding)

Don Francisco showed us some banana trees he had. He also planted banana trees in the forest. His theory is that if the monkeys have bananas for themselves in the forest then they will leave his banana trees alone. He showed us where a bunch of bananas had been cut off and stolen and joked that some monkeys with machetes had come to take his bananas.

Bananas

A nest

While near the jungle, Francisco proudly showed us a tiny plant. At first I could not imagine what kind of rare and valuable plant it was that he took such pride in. Coca, that's what. He somehow got a seed or a cutting (probably a seed) and this is his one, precious coca plant from which perhaps some day he can grow his own coca leaves for chewing.

Coca

I have two last pictures that don't fit very well in this story, so I am throwing them in here. The road was DUSTY. Horribly dusty. It was a dirt road and every vehicle that passed kicked up a huge cloud of dust. Check this out:

You might have noticed that when I called this "responsible" soy - which is how it was presented to us - I put the word "responsible" in quotes. It's not because Francisco is doing anything wrong. He's amazing, truly. But this land was all forest and it was all cleared. As was all of the other land for miles and miles around.

A major problem in Bolivia is that instead of redistributing land that is already in agriculture, they let the super-rich keep what they have and then help the poor clear more forest to grow food. With these 16 hectares Francisco is a smallholder. The average large landholder in Santa Cruz has 16,000 hectares. That's average! When I was visiting corn and soy farms in Iowa, the average farm in the area I visited was only about 1000 acres, or about 400 hectares. And the land isn't even used very well. We were told that the cattle ranches here will have about one cow per five hectares, which is far more land than you need per cow.

The colonization and deforestation of the eastern lowlands of Bolivia were actually a U.S. brainstorm, dating back to the "Bohan Plan," a plan written in the 1940s (I think) by an American that more or less instructed Bolivia to do exactly what they did. And Bolivia, after its 1952 revolution, followed that advice.

No comments:

Post a Comment