On our seventh day of the trip, our trip came to a crisis point. There was a blockade on the road we needed to take that had now gone on for a week, and it seemed like it would not end in time for us. What would we do? Meanwhile, we had a long, hot drive from Rurrenabaque to Sapecho, which was interrupted by what seemed to be another blockade. WTF, Bolivia?

My trip was organized by Global Exchange and Food First. You can find out about future Food Sovereignty tours at the link.

Shortly after we arrived in Bolivia, a blockade was announced in Yungas - right in the middle of our trip route. We had changed the order of our trip so that we would hit the blockade at the end of the trip instead of in the beginning, hoping the blockade would be over by then. It wasn't. At this point, we commissioned a few cars and drivers in Rurrenabaque to drive us to our next stop, Sapecho, and hoped we would be able to continue on our planned route from Sapecho to Caranavi, then Coroico, Chulumani, and back to La Paz. But it seemed pretty doubtful.

Daniel promised that our drive to Sapecho would be "long, hot, and dusty." I hoped he was wrong. When our three minivans showed up to drive us, I polled each of the drivers on whether their cars had air conditioning. Nope, no air conditioning. In fact, at this point, fuel was getting scarce on this side of the blockade, so even if there was A/C, we might not have been able to use it. Each of the drivers had large containers of gas in their cars to refuel with, in case the gas stations ran out.

Of course, Daniel was right about the "long, hot, and dusty" - at least for the first part of the drive. The road to Sapecho was mostly unpaved. Each vehicle we passed kicked up a huge cloud of dust behind it. Fortunately, traffic was low due to the cocaleros' blockade in Yungas, but we still passed several logging trucks. Strangely, we passed an area where there was roadwork going on. I didn't realize that dirt roads were the recipients of roadwork. I had assumed they were the result of a lack of roadwork.

The dirt road

Driving through the smoke from someone burning forest or pasture

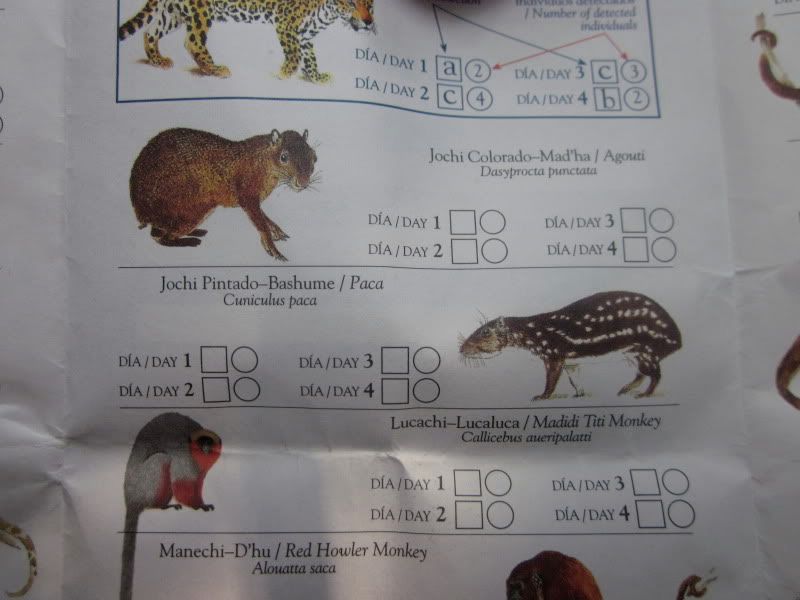

Despite the dusty roads, our driver drove as if he were escaping a crime scene. Several times, I was sure he was going to hit dogs laying in the road, or even people. I had resigned myself to the fact that I wasn't going to see any wildlife in the rainforest (now that we were leaving for Sapecho), but I was wrong. A jochi (a.k.a. agouti) ran across the road in front of us and thankfully was not hit by our driver.

The two species that Bolivians call "jochis" - one is a paca and the other is an agouti

We came to a town that Daniel says always looks like an earthquake just hit it (it was a bit run down) and everyone stopped for bathroom breaks and snacks. I think the town was called Yucumo. While we were there, it began raining a little bit - good news to everyone who was worried that the rains were late this year, although just because it was sprinkling in Yucumo, that doesn't mean that it rained (or rained sufficiently) everywhere.

After that, we began to climb into the mountains, and the weather cooled down. We had been more or less driving around the 400,000 hectare (nearly 1 million acres or 1544 square miles) Pilon Lajas Biosphere Reserve, and now we came around the other side of it and, from the mountains, we could look down on it.

We came to a stop at about 1000m of elevation, on a mountain called Pilon. For whatever reason, this mountain gets a lot of moisture, and it was a birder's paradise. Daniel said that often birds were sighted here at their lowest recorded elevation. During our stop, I took the opportunity to get a close-up shot at a hanging nest, and then realized that this was a nest that was under construction as I watched the beautiful yellow-tailed birds fly to it with twigs in their beaks. These nests are so common in this part of Bolivia that often you pass trees that are literally full of them. (I've been told by one source they were Crested Oropendolas, and another that they were Yellow-rumped Caciques. Maybe we saw both. The picture of the Crested Oropendola looks like the bird I actually saw in Bolivia that was building these nests.)

A hanging nest

Tree with many hanging nests

From this point on, the drive got downright pleasant. We passed through a town called Cascada ("Waterfall") that had a cascada - albeit a small one - and saw an absolutely gorgeous sunset. We drove over a road paved in stones (which was bumpy but better than dirt) and Daniel said we could thank our U.S. taxpayer dollars for it. The road was intended to discourage cocaine production, he said. "Did it work?" I asked sarcastically. Nope. Of course not. The coca growers were like "Thanks for making it easier for us to take our coca to market on our nice new road!"

All of a sudden, we could hear a loud, shrill noise. It could have been the background music to a horror movie. It was the sound of cicadas. Then insects in the rainforest are audibly loud throughout the day, but this was something else.

A view from Pilon

It was soon after the cicadas began that we came to the "blockade." I put it in quotes because it turned out that it was not a blockade at all. But this is Bolivia, where road blockades are practically the national sport. If you have something to protest, you go out and blockade the roads. So when everyone came to several cars stopped and people in the roads, we stopped.

As it turned out, it was nothing more than a funeral of some sort. I don't know what they were doing in the middle of the road, holding up traffic. Someone from among their group began handing out bottles of Coca-Cola to the people who had stopped and got out of their cars. Our drivers each accepted one. Even once it was clear that this wasn't a true blockade, no one wanted to be the first to drive through it. Finally, a big rig truck had had enough waiting around, and he drove through the crowd. Then everyone else followed. Phew. Our Bolivian "blockade" experience was just a no-big-deal fake.

The "blockade"

Well, at least, THAT blockade experience was no big deal. The real blockade - the one in Yungas - THAT was still going on. The road from Sapecho to Caranavi was clear, but with the blockade happening somewhere in between La Paz and Caranavi, our minibus could not make it to Sapecho to pick us up. We had to come up with alternate plans for the rest of the trip.

Rurrenabaque, at this point, was beginning to run out of things. There was not much gasoline left, and someone told me they were out of carrots. Also, farmers who grew fruits to sell in the highlands were now having their fruit go rotten before they could sell it. The blockade was becoming a disaster for Bolivians who were caught behind it.

Tanya, our guide from Food First, told us our new plans as we ate a homegrown, organic, and DELICIOUS dinner in Sapecho (at an agroforestry operation that we also visited the next day, which I will cover in a future diary). Tomorrow, as planned, we would visit the El Ceibo chocolate cooperative in Sapecho. Then we would return to the agroforestry operation for lunch and a tour. That much was in our original itinerary.

It was after that the plans had to change. We would drive back to Rurrenabaque and spend the night there. Early the next morning, we would fly to La Paz, get in a minibus, and drive to Oruro, spending one night there. Then we would return to La Paz for the rest of the trip.

The change in plans ruined the continuity of our trip, which was intended to show the various agroecosystems as one travels through each different altitude from the Altiplano to the Amazon, but at least now we would see some llamas.