We spent our fourth day in the indigenous community of Santiago de Okola, on the shores of Lake Titicaca. I've already written up the weaving workshop and agricultural Q&A we participated in that day. This diary covers everything else we did that day - including a spectacular lunch of indigenous Andean foods.

My day began early, before the sun came up. I'm not sure which woke me up first - the rooster, or my bladder - but once one of them got me up, both of them kept me up. I waited until it was light out because I did not want to attempt balancing over a hole while holding a flashlight to make sure I wasn't peeing on my shoes.

When I finally got out of bed and went out to do my business, my host family was busy taking their sheep out to pasture. I watched as the flock followed Don Pasqual to the field, with the newest baby, only a week old, struggling to climb up a few rocks on the way (Don Pasqual lives on a small hill). Once the baby had succeeded in climbing over the rocks, the rest of the flock was out of sight, and both the mother and baby were lost.

I must admit, for me this was a bit of a dream come true. I love animals. Especially cute baby animals. I took the mother sheep by her leash and helped guide her out to the field with the rest of the flock. The baby followed along. Don Pasqual was in the field, securing each sheep's leash with a stake, and he hollered a thank you for my help. I watched as the mother and baby joined the flock, wishing I could help more (or, better yet, pick up the baby and cuddle him like I do with my cats). Finally, I went back to my room to change into my clothes for the day.

A little later, Don Pasqual knocked on my door. "Desayuno," he said. Breakfast. I got up and walked over to Lucia's house, next door. Don Pasqual and Lucia had made a deal that she would serve both Tanya (her guest) and me the first dinner and breakfast, and Don Pasqual would serve us the second dinner and breakfast. Lunches were eaten together with the entire group.

I arrived to Lucia's to find a beautifully set table and Tanya waiting for me. She told me that she woke up and looked outside, only to see me out in the field tending the sheep. I smiled, and promised to show her "my" sheep after breakfast.

Breakfast was (mostly) nothing to write home about. We were served coca tea, Nescafe, white bread rolls, margarine, jam, and a delicious fried quinoa tortilla-like food. Lucia was doing the best she could with limited resources.

After breakfast, we joined the group for a weaving demonstration and a discussion about the community's agriculture. A few members of our group said they were served a delicious food called quispiña for breakfast. (I found a recipe for it here.)

Breakfast

A view of Lake Titicaca during breakfast

Lake Titicaca again

A pile of large bags in front of Lucia's house. It seems that she and everyone else in rural Bolivia buy their flour and rice in bulk.

That day, I forgot to wear a hat. It didn't take long for me to get sunburnt. We were about 13,500 feet up, and I had just begun taking malaria medication that makes you more susceptible to sunburn. During the weaving workshop, the group began to comment on how my face was turning red. I put on my sweater and borrowed a hat from Tanya (thank you Tanya!). By lunch, the little bit of skin that was still exposed - on my hand - was turning red.

Fortunately, we ate lunch in the shade. Like the day before, lunch was incredible. They served us more food than we could ever eat, and most of it was absolutely delicious. First, they served us roasted banana, oca, sweet potatoes, and potatoes. Then they brought us a plate of beef, which I did not eat (others did). During the meal, I snapped pictures of the leg warmers worn by the cholitas (I don't blame them - it gets COLD in the Andes) as well as the typical cholita hairdo (they wear their hair in braids, which are often tied together by a black string adorned with tassels).

Lunch coming out of the oven

Lunch. From the top and going clockwise: Potatoes, bananas, sweet potatoes, and oca.

Check out those leg warmers

A typical cholita hairdo

After lunch, my day was pretty much over. I was burnt to a crisp and even though I would have liked to join the others seeing a nearby church with a beautiful painting or hiking up Sleeping Dragon (the mountain next to Santiago de Okola), I needed to get out of the sun. I made plans to hike Sleeping Dragon with some members of the group after the sun went down a little, went back to my room at Don Pasqual's house, and fell asleep.

Many of the things in Santiago de Okola are homemade, including this ladder.

There's really nothing to do with plastic bottles, since there isn't any recycling and I doubt there's trash service.

I woke up several hours later to a knock on my door. My friends had forgotten me and hiked the mountain without me. They offered to hike back up it with me if I wanted. No way. At some point, we walked back towards Don Tomas's house to debrief on our time in Santiago de Okola.

We talked about the challenges for the people of Santiago de Okola of retaining their traditions into the future. Many of the people who had hosted us and shared their culture with us were grandparents. Their children and grandchildren were more likely than them to move to the city, speak Spanish instead of Aymara, and abandon traditional Aymara clothing and traditions.

Our Bolivian guide, Gabriel, told us that a major problem for indigenous cultures was the one year of mandatory military service for all Bolivian men. The military still has a racist, anti-indigenous culture that makes many men ashamed of their language, traditions, and even skin color. But Gabriel has high hopes for Santiago de Okola. There's a young man in the community who he sees as a future leader, and by organizing into an eco-tourism operation, the community is able to generate enough income to stay on their land and to retain their traditions.

We asked Gabriel about other Andean highland communities. He was less sure about those. He's familiar with several eco-tourism operations, but the indigenous communities in Bolivia are rather suspicious of outsiders, and as a non-Aymara speaker and an urbanite, Gabriel would be considered an outsider to rural Andean communities.

This flag, known as the wiphala, represents the indigenous people of Bolivia, and it is officially one of two flags of Bolivia (along with the red, yellow, and green Bolivian flag)

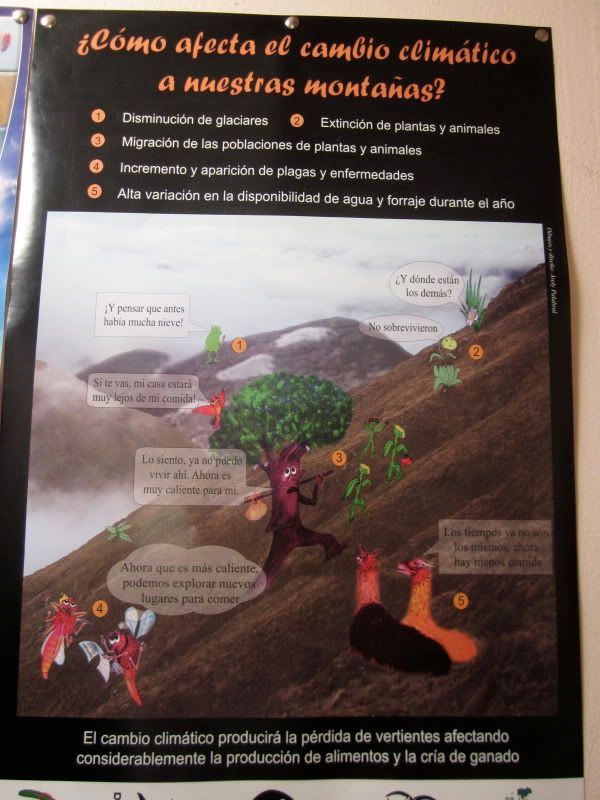

A poster showing the impacts of the climate crisis on the Andes

I spent the rest of the evening hiding from the wind in my room, where Don Pasqual served me a delicious (and enormous) dinner of quinoa soup, potatoes, coca tea, and more beef. He served me the soup as the first course, so when he brought the second course, I was shocked that there was MORE food. I told him I was mostly full already but I would do my best. Then I asked him if he had a refrigerator, since it seemed to me that there would be no way to handle so many small cuts of beef over a several day period without one. And I didn't know the Spanish word for freezer. He said yes, they had a fridge. (He also has a minivan - I'm not sure if it's his personally or if it belongs to the community - and several members of the community have cell phones.)

After dinner, I went to sleep. The next morning, we were leaving early for La Paz and going straight to the airport to fly to the Amazon.

No comments:

Post a Comment