We spent our fourth day in the indigenous community of Santiago de Okola, on the shores of Lake Titicaca. We began with a weaving workshop, which is described below. (The workshop was surprisingly informative and wonderful, and I encourage you to take a look at this, even if it doesn't initially interest you. At the end, I also added some information from the last day of my trip, when I visited a museum in La Paz with a Bolivian archaeologist who explained even more about Bolivian weaving traditions.)

I can say for certain that I had no idea how important weaving is in Andean culture when I showed up at the weaving workshop. I like to knit, so I figured that learning to weave would be somewhat similar to learning to knit - except maybe harder. I was right that it's harder than knitting, but as it turns out, actually learning how to weave was not the important part of the workshop. (And I totally do not know how to weave now, although I understand in a very basic sense how it is done.)

When we arrived, a few elderly women were busy setting up. On one side, they simply secured their projects by driving a stake into the ground with a rock. On the side where they sat, they also drove stakes into the ground, but here they attached ropes that they then pulled as hard as they could, using their legs and bare feet for leverage. You can see this in the pictures below.

Driving a stake into the ground

This is a two person job.

She's using her bare feet to pull the rope as tight as possible, while he helps her with it.

With that done, the women began weaving. They spent most of their time making sure that each row was woven tightly, and relatively little time actually weaving each new row. Weaving involves passing a horizontal piece of yarn in between two sets of vertical rows of yarn (one above and one below the horizontal yarn). The horizontal yarn, the color of which is not important, is completely covered on both sides by the vertical rows of yarn. Then the new row is tightened using a tool made from a llama bone, and the vertical rows of yarn are switched so that the strands that were previously on top are now on the bottom, and those that were on the bottom are now on top. And then the next horizontal row is passed through and the process repeats. All in all, it's incredibly time consuming and physically demanding as well, since one must work hard to make sure that each row is as tight as possible. And yet, we were told that the women who were demonstrating their skills to us could finish the weaving projects they were showing us in just 10 days.

Weaving

A second woman demonstrating weaving.

Tools made of llama bone.

As the women wove, one of the men of the community showed us some of their community's more important examples of weaving. When he spoke, he referred to the women who weave as "our grandmothers." As it turned out, THIS was the most interesting and significant part of the workshop.

Examples of weaving - the ones toward the left use natural dyes, compared to the brighter ones on the right.

More examples of weaving

He began by showing us undyed bags made of llama fiber (most of the other examples were made from sheep's wool). The small one is a llama bag, the large one is a donkey bag. These bags are exactly measured out to the amount of cargo each animal can carry. I'm sure you can see why Bolivians have adopted the use of donkeys once they were introduced by the Spanish. They've still got plenty of llamas, but so far as I can tell, the llamas are now used more as food than as beasts of burden.

Donkey bag (left), llama bag (right)

Then he showed us an onda. This is the traditional sling made and used by Andean men. At one end, the onda has a loop to put one's finger through. In the middle, it has a thick part that holds a rock. To use it, you swing it around in a circle and then, when you are ready, release the end that isn't attached to your finger, and the rock goes flying.

An onda

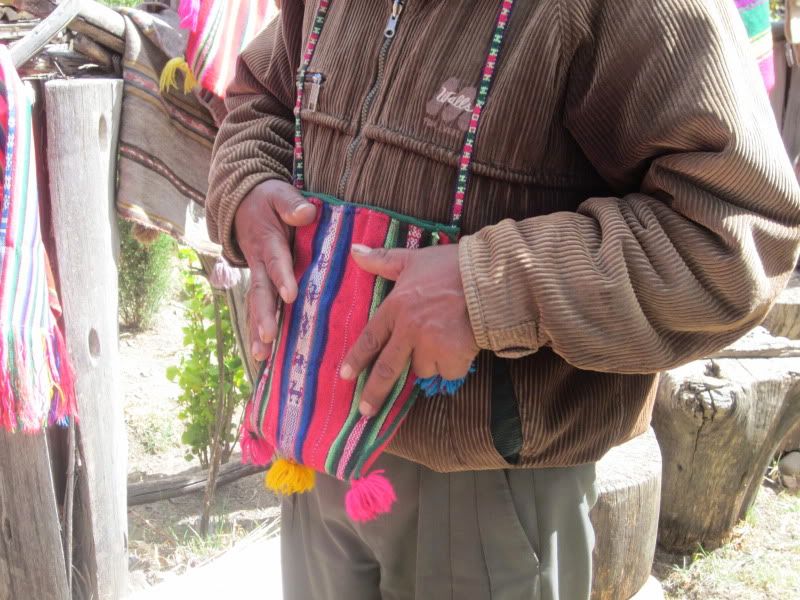

Next up, a traditional bag carried around the neck by the male leader of the community to carry coca. He also showed us a similar, larger bag carried by the leader's wife.

Male coca bag

He then showed us some undyed fabric, which would have been used in the past to make clothing out of. He also showed us a skirt that was made of woven fabric. Today, clothes are typically purchased instead of made by hand. I heard from one source that the beautiful, often ornate, fabrics used for cholita women's skirts now comes from Korea.

Undyed fabric

A traditional cholita skirt (pollera) that would have been made from that woven fabric in the past.

In Bolivia, the leaders of communities are identified by ponchos, but each region wears a different color poncho. Santiago de Okola falls in the region that wears red ponchos, and so does the town we stopped in (where I found the DDT), Achacachi. Because Achacachi is known as a town of warriors, to say that someone is a "red poncho" means that they are a badass. When we traveled to Oruro, we saw a man - the leader of his community - wearing a green poncho identical to the red one here. These ponchos are woven so tightly that they keep out the wind and the rain incredibly effectively.

A red poncho for badasses

For special occasions, women sometimes weave names and dates into their designs. The man who was leading our session showed us one woven cloth made by his wife to commemorate the year he was the leader of the community. The community leadership position is not permanent, nor is it elected. It is a rotating position each year, and everyone gets a turn. When it's your turn, it's a big deal - and that's why his wife commemorated his turn with such a special weaving. This year, he told us, nobody wanted the job. Because nobody wanted it, they took the unusual step of selection someone - Don Tomas - to be their leader. I don't know if selecting Don Tomas involved a vote or merely a discussion and a consensus.

Another example of an elaborate weaving with names and dates woven in was a wedding gift for Don Tomas and his wife. It included both of their names and the year, 1973. It also included the patterns of the ancient paintings we saw on the beach the day before, and pictures of several animals.

A wedding gift for Don Tomas

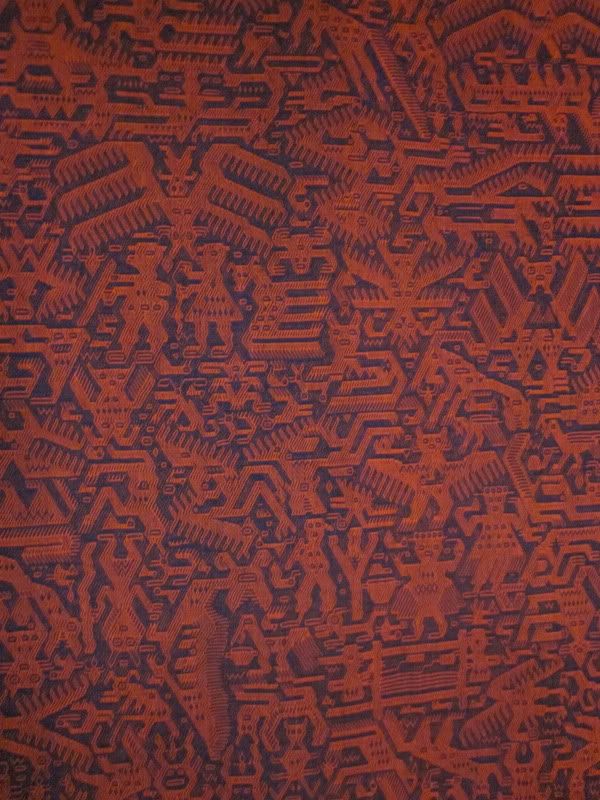

It blows my mind how one can weave names, dates, and animals into a cloth like this. On the last day of my trip, I visited the Museo Nacional de Etnografia y Folklore in La Paz, where I saw an even more ornate weaving:

A weaving at the National Museum of Ethnography and Folklore

I visited the museum with a Bolivian archaeologist (the same man who was our guide at Tiahuanaco), and I was amazed at what he could tell about a weaver or a community simply by looking at a woven cloth. He told us that when various groups came together for festivals, each community could be easily identified by the woven clothing their members wore. He could easily tell just by looking at a weaving whether the weaver was male or female, from the highlands or lowlands, whether a woman was single or married, and what type of agriculture was practiced in that community. Some of this could be determined by the colors used, or whether the weaving used horizontal or vertical stripes.

What I thought was most interesting was how the weavings represented one's community and environment and one's relationship to it. A woman, for example, tended to leave large fields of solid color in her weavings to represent the "pampas," or areas of wild savanna around her. To her, the pampas was mysterious and undefined. However, a man might not show any mysterious pampas in his weaving, instead weaving stripe after stripe with no large blank areas, because he was not afraid to travel through the pampas.

The smaller stripes in a weaving represent the cultivated farm fields. A woman who felt that her community had a lot of farm fields with relatively small areas of pampas would weave clothes with many small stripes and small areas of solid color. And a woman in a community that raised more animals than crops would weave designs of animals into her stripes that represent cultivation in her community.

As you walk around the museum, you can see that the colors of dyes used in older textiles are not nearly as bright as the dyes used today. The man leading our workshop told us that today, they use aniline dyes instead of the natural ones used in the past.

The last thing we did before trying our hands at weaving was select a few members of our group to dress up as the leaders of a community. We asked if only men could be the leaders, and they said yes - unless a woman is a widow. The reason is because both members of a married couple are expected to serve as leaders, even though the actual named leader is the man. If a woman has lost her husband, then she can serve as a community leader because her husband isn't there to represent the couple. We quickly selected a married couple of professors who were on our trip to serve as our "leaders," and the indigenous men and women who were our hosts quickly got to work dressing them up. And, last, we each got to try our hands at weaving. I'll be honest - I felt totally helpless and gave up after about 2 minutes.

Members of our group, dressed as Andean community leaders

Me, attempting to weave

Today, our hosts lamented, young people often prefer store bought items to hand made ones. Instead of carrying traditional woven awayos, they are more likely to carry their things in plastic bags. Still, it's impossible to venture outside of the airport in La Paz or go anywhere else in Bolivia (at least in the areas we visited) without seeing many people in traditional dress. The full ensemble doesn't come out on a daily basis, but that doesn't mean that the traditions of the past are gone. They are still very much present in modern day Bolivia. Indigenous communities are worried about whether young people will adopt these traditions, as some young people do choose modern dress over traditional dress, but for the time being, these traditions are quite alive and well.

No comments:

Post a Comment