When FOBOMADE told us they were presenting on TIPNIS, I was not sure what to expect. TIPNIS - the Isiboro Sécure Indigenous Territory and National Park - is a protected area (for environmental reasons) that is also a TCO, a Tierra Comunitaria de Orígen, or an indigenous territory. Thus, the land is twice protected - once for environmental reasons, and once because it is an autonomous indigenous area. Yet the Bolivian government is planning, against the will of the indigenous, to build a highway right through it. The issue turned out to be MUCH more interesting and complex than meets the eye.

TIPNIS was originally created in 1965 as a national park. At the time it was just PNIS, because it was not yet an indigenous territory. Then, in 1990, it was established as an indigenous territory, expanded, and renamed TIPNIS. The area then contained 1,225,347 hectare.

TIPNIS is a region of Andes to Amazon transition ranging in altitude from 3000m to 189m and including land in the provinces of José Ballivián, Marbán and Moxos in the department of Beni, and Ayopaya and Chapare provinces in the department of Cochabamba. Within the area are many different ecosystems and a wealth of biodiversity.

FOBOMADE says the following about TIPNIS:

Its forests regulate the water runoff on the plains and regulate the climate in the surrounding highly productive valleys; while large areas of wetlands, swamps and bogs play an important role in the regional hydrological functioning. This region records the highest amount of precipitation in all of the country, from 5700mm/year in Villa Tunari to about 3500mm/year towards San Ignacio de Moxos.

This territory faces serious threats from the spread of coca cultivation, drug trafficking, oil exploration, logging and commercial and sport poaching.

As early as 1992, the indigenous were negotiating with colonizers over where the colonization within TIPNIS must end. Representing the colonizers was none other than Evo Morales. In 1994, they agreed upon a Red Line that divided the indigenous territory from the area settled by colonizers. But conflict between the groups continued. In 2004, there was a proposal to redefine the Red Line.

In 2008, the indigenous and the colonizers finally agreed to the location of the Red Line that limited future settlements. However, that same year, Morales announced the awarding of the contract for the construction of a highway between Villa Tunari and San Ignacio de Moxos, right through the middle of TIPNIS, to the Brazilian company Constructora OAS Ltda.

Efforts to build a road in this area began in the 1990's. The groups interested in the completion of the 306km highway include neoliberal governments, political groups with interests in logging and ranching, oil companies, and colonists (likely coca growers) in the Chapare region seeking access to new farmland. Of course, during that time, Bolivia was under a neoliberal government.

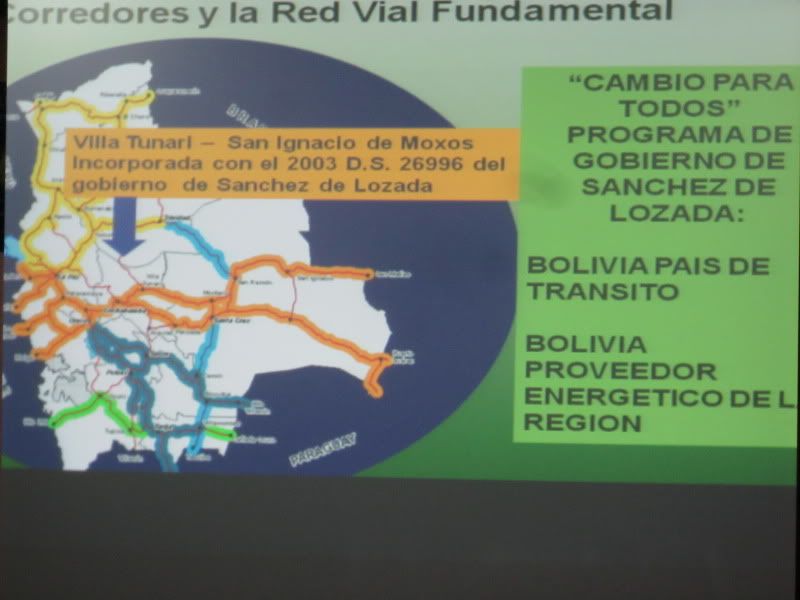

The hated, neoliberal Goni had a development plan called "El Cambio para Todos" (Change for All), which led to Decreto Supremo 25134 of 1998. The Supreme Decree established a national road network consisting of 10,401km of roads, including some mega highways. FOBOMADE accuses the plan of prioritizing the needs of Bolivia's international neighbors over the needs of Bolivians. Building roads needed for Bolivians was left to local governments, who did not have the funds to do so. FOBOMADE feels that the plan was designed according to the powerful business interests, without reflecting the needs for roads linking regions of Bolivia.

In 2000, under neoliberal president and former Bolivian dictator, Hugo Banzer, Bolivia joined onto the project of IIRSA, the Initiative for the Integration of Regional Infrastructure in South America. This was a plan that rose out of a meeting of South American presidents in 2000. It calls for an integration of South American infrastructure to make trade easier among and through each of the various countries. Here's a picture of all of the roads Bolivia has built or plans to build:

In the map, the blue roads are functioning, yellow exist but in terrible condition. All in all, about 30% of the roads on this map exist in a functional way.

The plan for a road between Villa Tunari and San Ignacio de Moxos was announced in 2003 under Goni, shortly before the Bolivian people forced him out of office. His vice president and successor, Carlos Mesa, continued with the plan, seeking financing for construction of a road linking the cities of Cochabamba and Trinidad in late 2003.

Looking at the big picture, Bolivia sits in the middle of many other South American countries. Starting in the north and working clockwise, Bolivia borders Brazil, Paraguay, Argentina, Chile, and Peru. Brazil, now the top soybean producer in South America, engages in massive soybean exports to China. Much of the soybean growing is centered in the Brazil state of Mato Grosso, which borders the Bolivian state of Santa Cruz. To get its soybeans to China, Brazil needs to take them across Bolivia to ports on the Pacific coast.

Even where there are roads in Bolivia, they are often terrible. In some places the roads are made of dirt and in some places the roads don't exist at all. Bolivia's lack of roads - and lack of good roads - are one of the reasons why the Bolivian people are so effective at exerting their will by blockading the roads. There often isn't another road that drivers can use to go around the blockade.

Brazil wants an East-West road through Bolivia and a North-South road through Bolivia to reach ports in Peru and Chile. It currently takes Brazil $1900 and 45 days to send 1 container from its Atlantic coast to the Pacific coast through Bolivia. With all of Bolivia's planned highways, it will take only $1260 and 4 days. Additionally, Brazil wants to get at Bolivia's Amazon. They are buying an awful lot of land in the industrial agriculture area in Santa Cruz too. Currently, 40% of Santa Cruz agricultural lands are in foreign hands.

Thus, since 2003, this highway has been part of the plan to link Brazil to ports in Chile and Peru through Bolivia under IIRSA. It runs parallel to the Sécure Oil Block, which the oil company Repsol has operating rights for (from a 30 year agreement signed with the neoliberal government of Bolivia in 1994). And even through Bolivians threw out the presidents who were pushing the construction of this highway (Goni and Mesa) and elected Morales instead, Morales continues to follow the same agenda as his predecessors.

The highway is to cost $415 million dollars, 80 percent of which will be financed by the Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES). The financing was secured with an agreement between Brazil and Bolivia in August 2009. FOBOMADE says, "The government of Evo Morales chose to build the road bypassing technical and environmental standards, national legislation, and especially the rights of the indigenous peoples established in the constitution." They feel that this project is being done more for the needs of Brazil than Bolivia.

FOBOMADE has a long explanation of the harm that will be done to TIPNIS if the highway is built. There will be logging, oil exploration, cattle ranchers entering from the north, and coca growers from the south. Brazilian transnationals will benefit, and Bolivia will be flooded with more Brazilian products displacing Bolivian ones in its markets. And indigenous autonomy and rights will be utterly violated.

While I was in Bolivia, some 1500 indigenous people began marching from Trinidad to La Paz, demanding to speak to Evo Morales and ONLY to Evo Morales. As of a few days ago, they had marched 70 of the 375 miles and tensions were high:

Upon their arrival in San Ignacio de Moxos, the marchers were welcomed by local residents but also confronted by a mob of campesinos, cocaleros, and other MAS loyalists who broke windshields of their support vehicles and initially blocked their exit route. Stores and public facilities were closed, depriving the marchers of access to food and water.

While the MAS government denied responsibility for these provocations, the government’s consistently disparaging remarks about the indigenous protestors created a climate of hostility that invited confrontation.

In other words, this is an ongoing controversy that encapsulates a number of different struggles Bolivia is going through. Deforestation of a precious protected area of high biodiversity is certainly important, but this also involves national sovereignty, indigenous rights, oil exploration, coca and cocaine production, and more.

No comments:

Post a Comment