Yungas is an Aymara word that means Warm Lands. Since Pre-Columbian times, the indigenous people of the Altiplano sent colonists to Yungas to grow crops that were impossible to grow in the Altiplano. Thus, they formed "vertical food archipelagos," trading along routes varying in altitude so that all could benefit from the bounty of many different ecological zones.

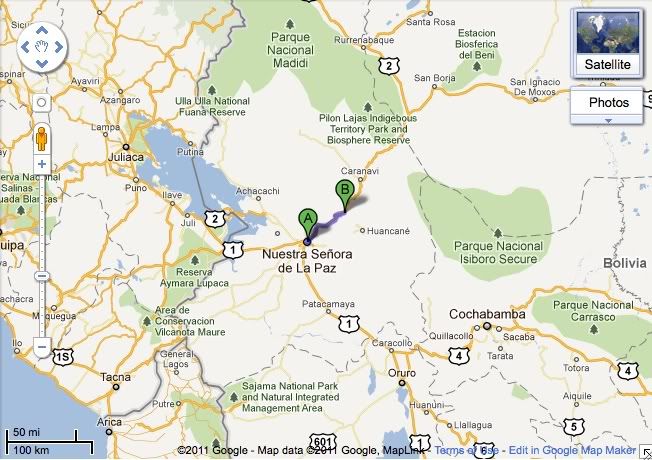

We were heading to a town called Coroico in the region known as North Yungas. Both North Yungas and South Yungas provinces are in La Paz department, but the Yungas ecosystem extends beyond that, in a strip along the edge of the Andes as they descend toward the valleys and lowlands. You can see in the map below where we were going:

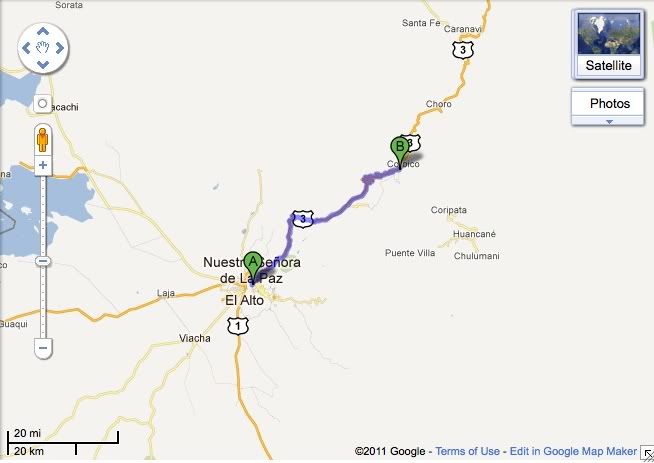

You might notice that the road extends all the way down to Rurrenabaque near Madidi National Park, just outside La Paz in Beni department, right as the Andes meet the Amazon. This was the road we were going to take last year - and the road that was blockaded, preventing us from doing so. You can also see Lake Titicaca to the west and Cochabamba (and TIPNIS) to the east. Here is a close-up of the road we took, showing Caranavi and Chulumani, which are other cities in Yungas:

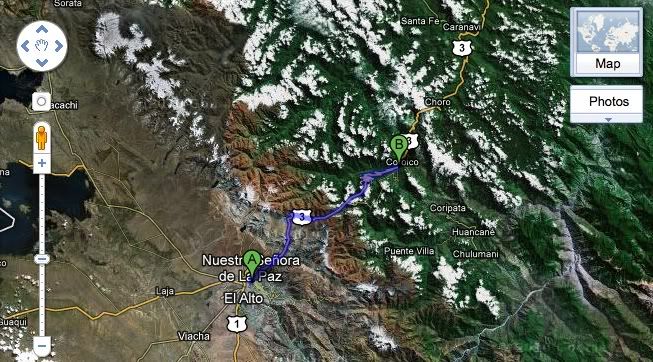

Now, check this out. Look at how brown turns to green as the Andes give way to the cloud forest all throughout Yungas:

Originally, we didn't plan to take the Death Road. I don't know whose idea it was, but I'm sure the driver had a lot to do with the decision. His name is Eloy and he was also our driver the year before. I asked him if he remembered me and, when he said yes, I thought surely he was just pretending - until he said the words "mosquito bites." Yup, he remembered me.

The Death Road was built in the 1930's, following Bolivia's Chaco War with Paraguay. Bolivia used Paraguayan prisoners of war to build the road. Since then, its been the site of numerous deaths - hence the name. A few years ago, Bolivia built a newer, better road to Yungas. Now the Death Road gets most of its traffic from cyclists who go out in organized tours to bike the Death Road. We saw the cyclists (wearing orange vests that said "I survived the death road," which I thought were a little premature, given the terrain and its difficulty) throughout our drive.

To reach Yungas, you do not exit La Paz through El Alto. We stopped at the edge of the city to shop at the Via Fatima market for marraquetas, a type of bread that was not available in Yungas. Our guide, Tanya, used to live in Coroico and we were going to visit her friends. For the community there, it was the duty of anyone visiting La Paz to buy marraquetas and bring them back for the group. (By U.S. standards, they weren't even that good - but Tanya assures us that they are far better than what is available in Coroico.)

Via Fatima happens to be the single location in Bolivia where coca may be legally sold. Yungas is the traditional coca-growing zone (now it has expanded into Chapare in Cochabamba as well), and anyone who grows and sells it legally must bring it to Via Fatima. There it is sold by the growers and then purchased by coca sellers from around the country who want to sell it for legal, traditional uses like tea, chewing, and rituals. As we arrived, there wasn't much activity around coca buying or selling.

Spices

Apples from Chile, imported legally or otherwise

Packaged goods.

A price list. I believe prices are per kilo. It's about 7 Bolivianos to one US dollar. Choclo is the Bolivian word for corn.

Eggs. The prices are in centavos.

Bread.

As we left Via Fatima, we began to go up. In order to reach Yungas, you must go over a range of Andes, up to a height of about 5000m (16,400 ft). It was going to get colder before it got warmer. As we ascended, we began seeing the same vegetation and livestock I remembered from Sajama National Park in Oruro - low, cushionlike plants such as Yareta, and llamas.

We stopped at the top for photos and found that we were not the only ones there. The bikers were assembling for their harrowing ride down, but many Bolivians were there too, making ritual offerings to Pachamama (Mother Earth). This practice, known in Spanish as ch'allar, is done in August, because that is the month when Pachamama is hungry and her mouth is open. Offerings are made on the tops of mountains, because that is where the gods are.

The remains of someone's offering

A view of the road down

Another look down. Check out the vegetation - it looks so barren.

Our group.

Look closely and you'll see a zigzag pattern going up the mountain. It's an old Incan road that is still visible.

And, almost suddenly, we're in a beautiful, lush, green cloud forest:

A look across at the road we're going to take.

A good place to go off a cliff. And yeah, it's happened.

Yungas is known for its many ephiphytic plants. An epiphyte is an organism that live together with another species, neither in symbiosis, nor as a parasite.

I think I took this picture because it was a good example of epiphytes, as there were other plants growing on this tree.

Me, with a biker behind me. I joked with Eloy that if we weren't lucky, he might accidentally have a death scene in this photo if any of the bikers went off the cliff.

I took several pictures of the vegetation along the road. There were many little waterfalls, almost like rain falling on the road.

The grave of a young Israeli who died here. Bolivia is a Mecca for Israeli tourists.

Waterfall

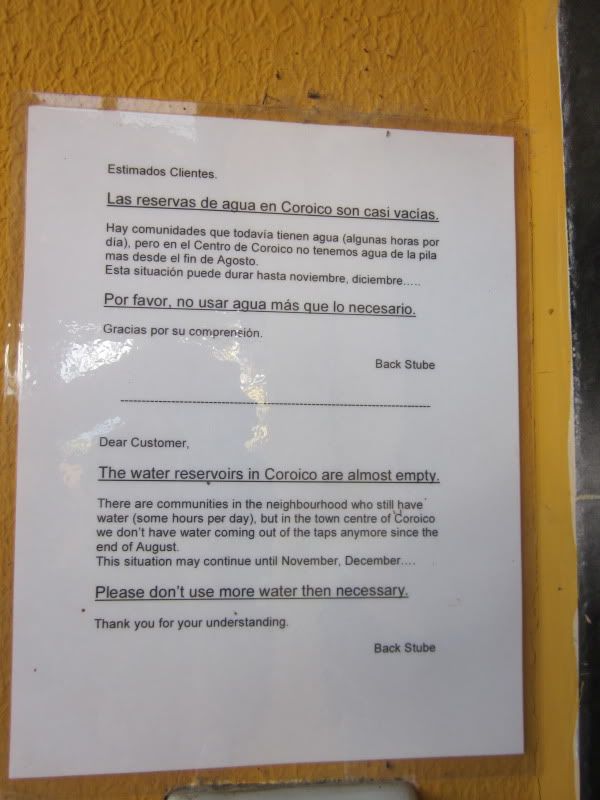

At last, the beautiful but hair-raising drive came to an end, and we arrived in Coroico. Built into the side of the mountains, it could almost be a Northern Italian village. We stopped for lunch, and I was taken aback by this sign near the bathroom sink in the restaurant warning us about the area's lack of water in its reservoirs:

The view from the restaurant

Before continuing to our hotel, we bought ingredients for dinner in Coroico. I was surprised to see a cholita of African descent:

I suppose I shouldn't have been so surprised. African slaves were brought to South America, especially after European and African diseases killed off so many of the indigenous and the Europeans attempting to enslave them. Throughout the Americas, some Africans escaped and integrated into indigenous communities or formed their own communities, some of which survive to this day.

Oca, an Andean tuber I particularly like

Isaño, another Andean tuber.

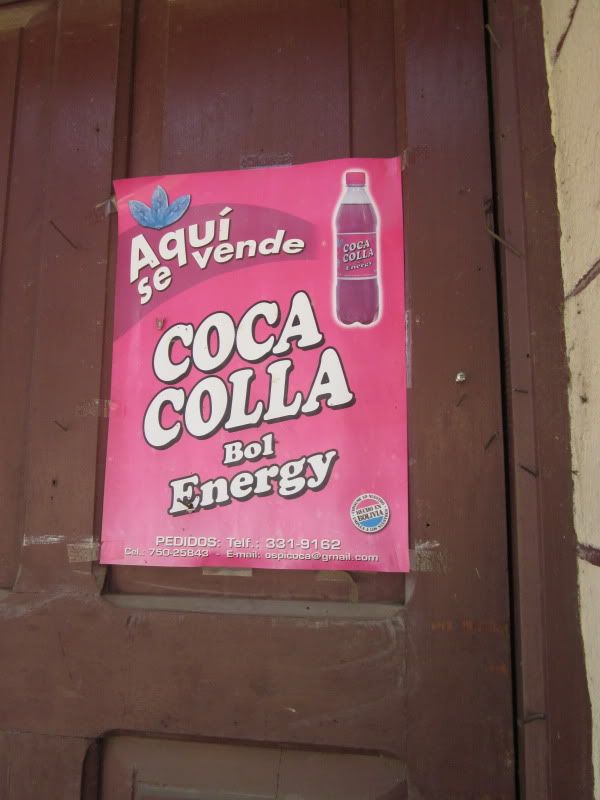

This isn't just an accidental misspelling. A "kolla" is a Bolivian highlander, a term derived from kollasuyo, the name of the Incan province that included Bolivia.

The next diary will be about our activities once we arrived in Coroico: harvesting and processing COFFEE!

No comments:

Post a Comment