The history of agriculture in La Paz goes back before the Spanish conquest of South America. La Paz is located in a valley in the Andes and it's a great location for agriculture. As such, it provided food for the Tiwanaku civilization before the Incan conquest. There are some 1600 documented pre-Columbian settlements in the valley of La Paz. La Paz then continued to grow food up until modern times when agriculture has mostly been pushed out of the city due to urban sprawl.

Once the Spanish showed up, they were after silver, and they found it in Potosi. But they had to travel to and from Potosi, carrying the silver on donkeys and mules, and needed to eat and sleep along the way. One of the two routes from Potosi, the one to Lima, went through La Paz. They established a walled Spanish city in La Paz and they would not allow the indigenous people inside the city. Because it wasn't considered dignified for the Spanish to engage in the market, the Aymara people became the tradespeople.

During this time, the Aymara evolved into groups like guilds. To this day, these guilds still exist and manage the commerce. They are grouped around the city with shoes in place, paint in another, electronics somewhere else. We headed to the food part of the city. Our guide, Stephen Taranto, told us that even a woman selling potatoes in a square meter on the street is paying someone for that spot and she's associated with an organization. Many of the sellers survive day to day, and each day's sales help them get by.

Here are my photos of the market. It was a Monday so the market wasn't very busy.

I love this picture because it shows how modernity (the woman in a suit) and tradition (the cholita next to her) live side by side here in La Paz.

One of the typical features of the markets here is the "casera" relationship. Customers become loyal to one particular seller, and they are one another's "casera." The seller will give her caseros a "llapa" (a little extra) with their purchase. It's kind of like a baker's dozen - you pay for 12 and the baker throws in one extra for you. Also, if the seller knows that her casero always buys 2 kilos of a certain type of potatoes, she will set them aside for him. And if he doesn't show up to buy them, she'll scold him. She'll also scold him if she sees him buying from another vender. While you walk through the market, venders call out to you, saying "Casera," hoping you will come buy from them and perhaps become their casera.

Peppers

Tunta, one form of traditional freeze-dried potatoes

Tunta close-up

Much of the food here is from within Bolivia, but not all. This woman is selling spices. I asked her where her cinnamon was from, expecting she would tell me it was from the Amazon. Nope, India.

Chicken eggs and quail eggs. Apparently the thing to do with quail eggs is hard boil them and eat them with "salsa golf," a mixture of ketchup and mayonnaise. No thanks!

With Bolivia's low trade barriers, they are increasingly flooded with imports, both legal and otherwise. You see an awful lot of perfect-looking red delicious apples around Bolivia. And no, they weren't grown here.

Apples from Chile, imported here legally... maybe.

Cargill wheat, likely from the U.S.

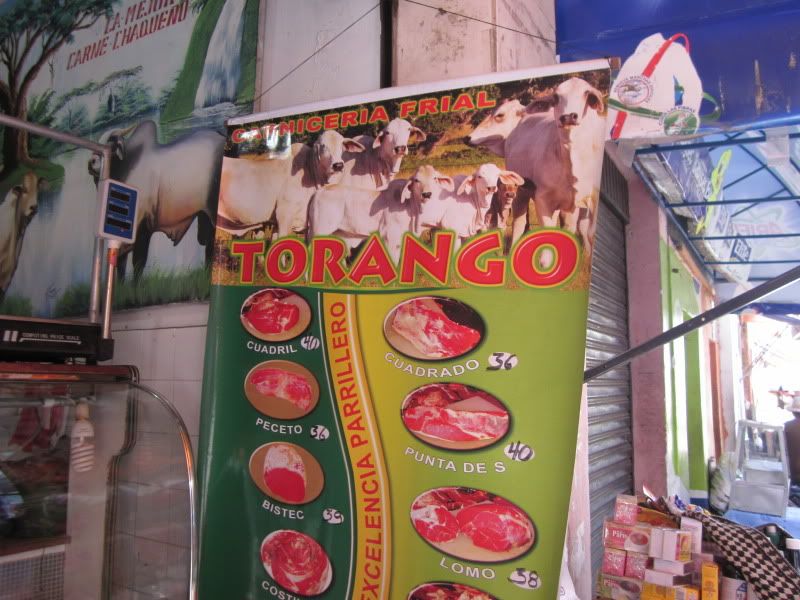

The market sells meat too. Sometimes in stores, sometimes on the street. Beef can come from either the Altiplano (La Paz department) or the tropical lowlands (mostly Beni and some from Santa Cruz), and it is often identified accordingly.

Beef from the lowlands

Beef from Santa Cruz & the Chaco, in the lowlands

These white cows are Green Revolution cows. I think these might be Brahman but there's another breed that is very popular in Bolivia's tropical lowlands that is also white. But I think the other breed has less droopy ears.

Meat on the street. Who needs a fridge anyway?

The dairy industry is a bit depressing in Bolivia. It's hard to produce milk in the tropics, but the Altiplano and Cochabamba do have quite a bit of dairy cows. However, the dairy industry is controlled by a foreign monopoly (Pil). Bolivia does not produce enough dairy for its own needs, and yet Bolivian milk is often exported, and powdered milk is imported into Bolivia. I think I've also been served milk from a can, which I did not drink, milk from a plastic bag, and milk from a box. Probably all ultrapasteurized. Bolivians often buy yogurt instead of milk because they don't have refrigerators. They just let the yogurt sit out.

Lots of potatoes

I hate Nescafe. But you can't escape it here. I go without coffee if my choice is Nescafe or nothing.

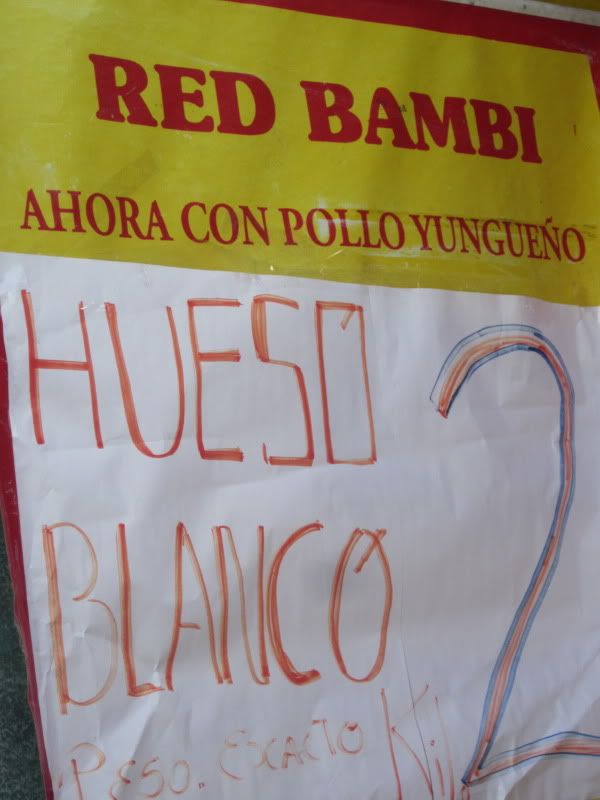

Chicken from Yungas. They produce a lot of chicken there.

There are now quite a few ecological food stores popping up around La Paz and other cities. Of course, what qualifies to someone in the U.S. as nutrition or ecological might not be the same as what qualifies in Bolivia. In this store (photo below), we found lots of Andean grains, products made with flax and sesame, far too much soy for my liking, El Ceibo organic chocolate, and yogurt. They also typically carry various types of tea, including many that promise health benefits via herbal medicine. In one natural foods store in Santa Cruz, I found Kraft Philadelphia cream cheese. God, that's sad if that's a natural food compared to Pil dairy products!

No comments:

Post a Comment